‘Hobo codes’ public art tracks the past alongside the present

In downtown Wichita, Jeff Best's Hobo Code Railings is tucked beneath an underpass. The art piece celebrates past nomadic life but permanently sits in a place where homelessness is present.

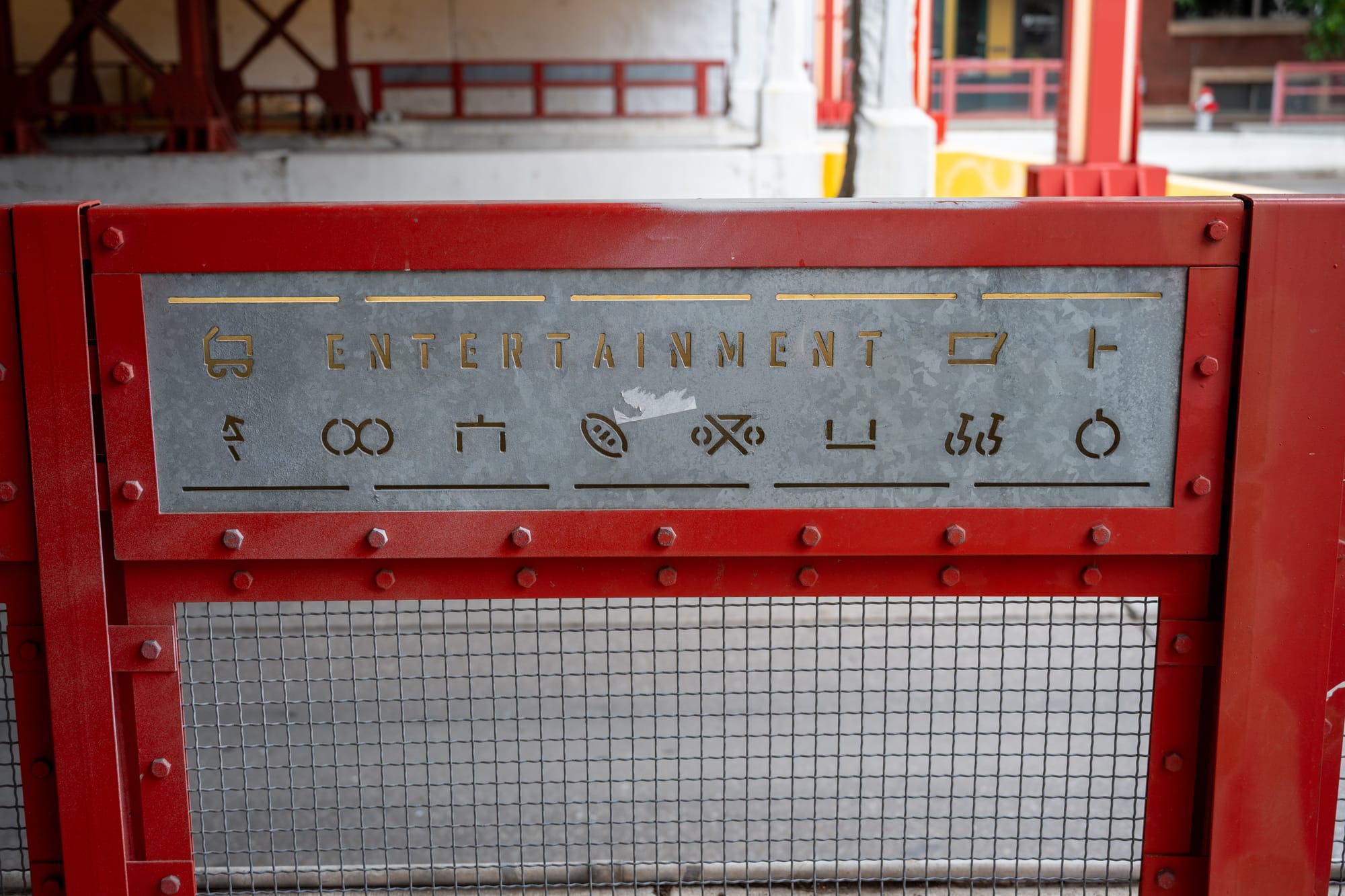

A constellation of stamped symbols hidden out of plain sight, the artwork Hobo Code Railings lives below the railroad underpass at Douglas and Sante Fe Avenues: no artist signature, no plaque, no glamour. There’s scant information online about this piece besides the name of the credited artist Jeff Best, who worked with LK Architecture to make the railings.

This art piece — understated, invisible to most passing by, stationed below an underpass — references past nomadic life but permanently sits in a place where homelessness can be present. Its location and attributes feel astute, riding the line between history and reality.

The hobo codes are on gray steel divided by attractive red metal, giving way to pleasing geometric lines framing the symbols. On the day of my visit, there was a makeshift bed a dozen feet away. Its maker was absent, but it made me wonder, where do your eyes go in a tunnel like this? Left to glyphics you don’t understand? Or right to a stranger you think you do?

Homelessness in Wichita is arguably the highest profile community issue. The city and county have devoted hundreds of thousands of dollars towards supporting homeless resources in recent years while residents have banded together to either voice their support or opposition to the cause.

As someone who reports on homelessness, I think people who see a homeless person and feel sympathetic or repelled share the experience of feeling something about a total stranger. We don’t know this person’s childhood, circumstances or choices. But, one way or the other, we perceive a whole human life into a singular symbol of hardship, whether we think the hardship is unjust or karmic.

How can we feel about hobo codes? The name of the piece is straightforward, polar to the art itself. There are some words floating between the slew of symbols – lodging, community, libations, commerce and entertainment – but the rest is abstract. Some symbols bear resemblance to everyday things (a train car, shovels) but the rest are lines playing amongst each other. There’s no key to what, exactly, you’re looking at, forcing the viewer to mull over the meaning behind each shape.

Subscribe to our free email newsletters

Stay in the know about Wichita's arts and culture scene with our Sunday news digest and Thursday events rundown.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

The placement of the Hobo Codes is a statement in itself. An underpass is a common home for an encampment. Homelessness is prevalent downtown, where the art resides. Hobo codes, historically, would also be found close to places of transit, especially railroads. Union Station, once a major stop for Santa Fe trains, sits behind the overpass. The codes are also (literally) bridging the neighborhoods of downtown and Old Town together, where libations, commerce and community (words etched into the art) run amok.

In the centuries of these symbols’ use, they have ranged from being meaningless squiggles to life-saving warnings. In Wichita, those simple, inconspicuous illustrations live under railroad tracks in an urban setting, parallel to the modern-day transient people who find sleep on a bed of brick.

The history of hobo codes

Hobo codes were secret markings left by vagabonds and other transient people, with a history tracing back to the 19th century. Hobos (as they were called back then) were usually men looking for work who would board trains to different parts of the country, likely following different harvest seasons or working in mining or lumber camps. They sought employment, freedom and independence, often leaning on trains for transportation.

Being strangers to most corners of the country, hobo travelers were often met with scorn or rejection. Locals thought they were lazy people searching for free handouts and were often discriminated against or assaulted.

As hobo travelers drifted in and out of towns, they began developing a sly form of communication to others like them: abstract symbols indicating welcoming homes, good jobs or good food. Nonsensical to most, life-saving for them. Hobos would use chalk or charcoal to mark locations, etching drawings onto walls, mailboxes and trees.

There’s no official record listing off every hobo code and their exact meaning, but an online search of them produces an endless amount of matches — its verification depending on the viewer’s acceptance.

A few of the Hobo Codes on Douglas are represented in this chart from the National Security Agency. “Fresh drinking water and safe to camp” is depicted by a squiggly line above two circles with an X between them. “Safe to camp” is three lines forming a rectangle missing its roof. An encircled X signifies “okay for a handout.” Two circles barely overlapping: “police frown on hobos.”

Other sources indicate that the double-shovels indicate “work available,” the loaf shape “bread,” and, my personal favorite, two parallel lines that mean “the sky’s the limit.”

The rest? I’m not sure. I could spend hours trying to line up the codes from various sources or filling in the blank with my imagination. But I kind of appreciate not knowing. Those messages were not for me.

Stefania Lugli is a reporter for The Journal, published by the Kansas Leadership Center. She focuses on covering issues related to homelessness in Wichita and across Kansas. Her honors include being a national finalist for a Nonprofit News Award in investigative reporting last year and a two-time fellow with the Solutions Journalism Network. The Kansas Press Association also recently named her one of 2025's journalists of the year.

Support Kansas arts writing!

The SHOUT is a Wichita-based independent newsroom focused on artists living and working in Kansas. We're partly supported by the generosity of our readers, and every dollar we receive goes directly into the pocket of a contributing writer, editor, or photographer. Click here to support our work with a tax-deductible donation.

❋ Derby man has the kind of voice that turns heads — and chairs

❋ Socializing while sober: how some Wichitans are cultivating alcohol-free communities

❋ As a small creative business closes, the owner mourns

❋ Painting through it: Autumn Noire on 20 years of making art

❋ How a guy from Wichita resurrected 'Dawn of the Dead'

❋ Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections

The latest from the SHOUT

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTEmily Christensen

The SHOUTEmily Christensen

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher