Still Here: Reclaiming place in ‘DoPiKa: Reinstate’

Works on view at Topeka's Mulvane Art Museum assert "a shared insistence on Indigenous presence as an active, shaping force." The exhibition is on view through November 15.

At the heart of “DoPiKa: Reinstate,” now on view at the Mulvane Museum of Art in Topeka, Kansas, is a deceptively simple proposition: that art can restore what history has obscured. This group exhibition, organized by the DoPiKa Project and led by Topeka’s Native-owned arts organization 785 Arts, features contemporary works by Indigenous artists Norman Akers and Sydney Pursel alongside selections from the Mulvane’s permanent collection. More than a showcase of individual talent, “DoPiKa: Reinstate” is a deliberate act of cultural re-centering — one that insists on the visibility of Native presence, both historical and ongoing, in Topeka and across the country.

From Left: Exterior of the Mulvane Art Museum; A close-up of the "DoPiKa: Reinstate" exhibition banner. Photos by Abby Bayani-Heitzman for The SHOUT.

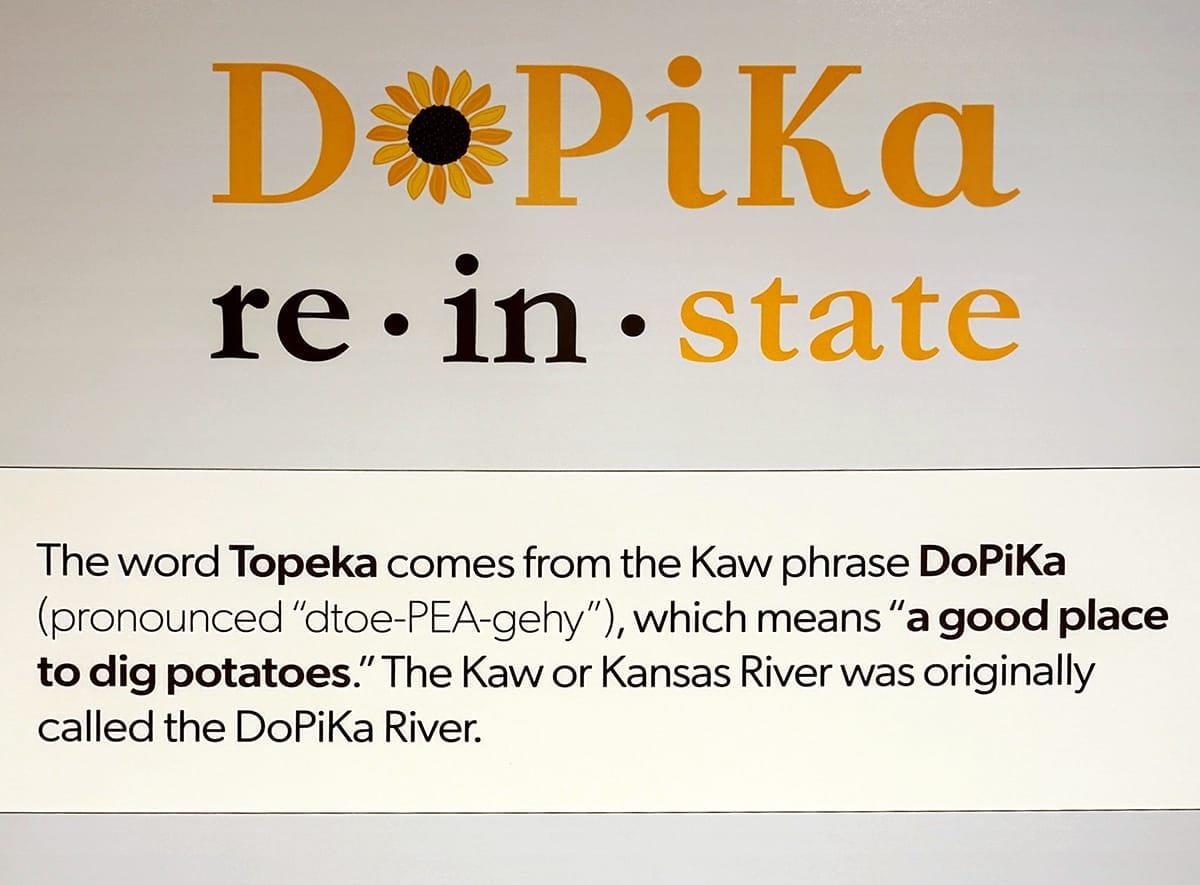

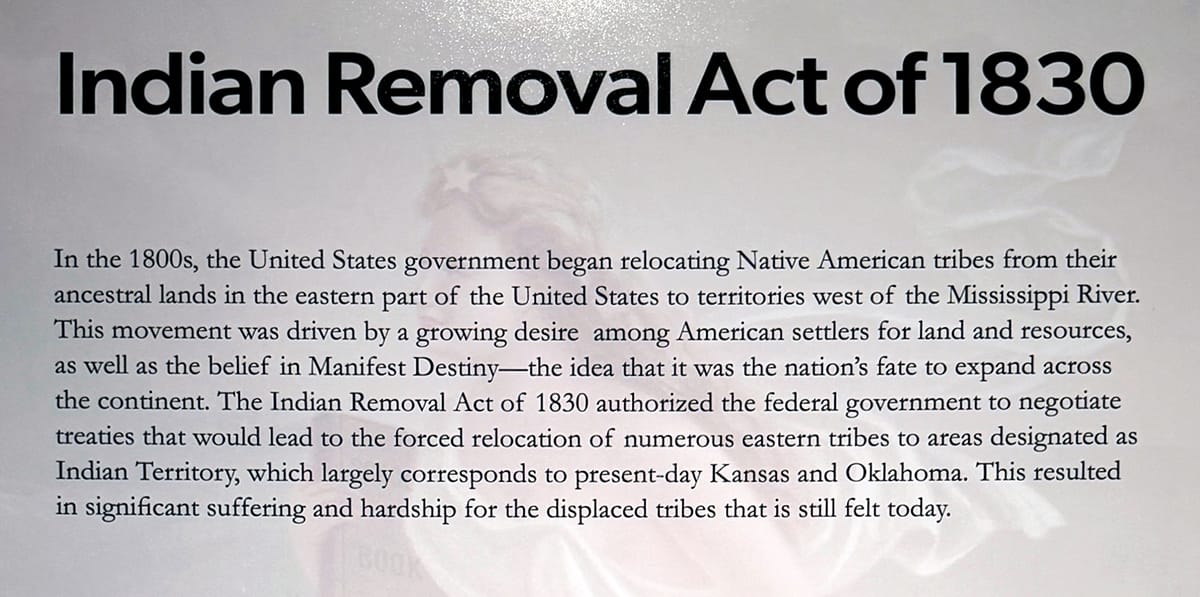

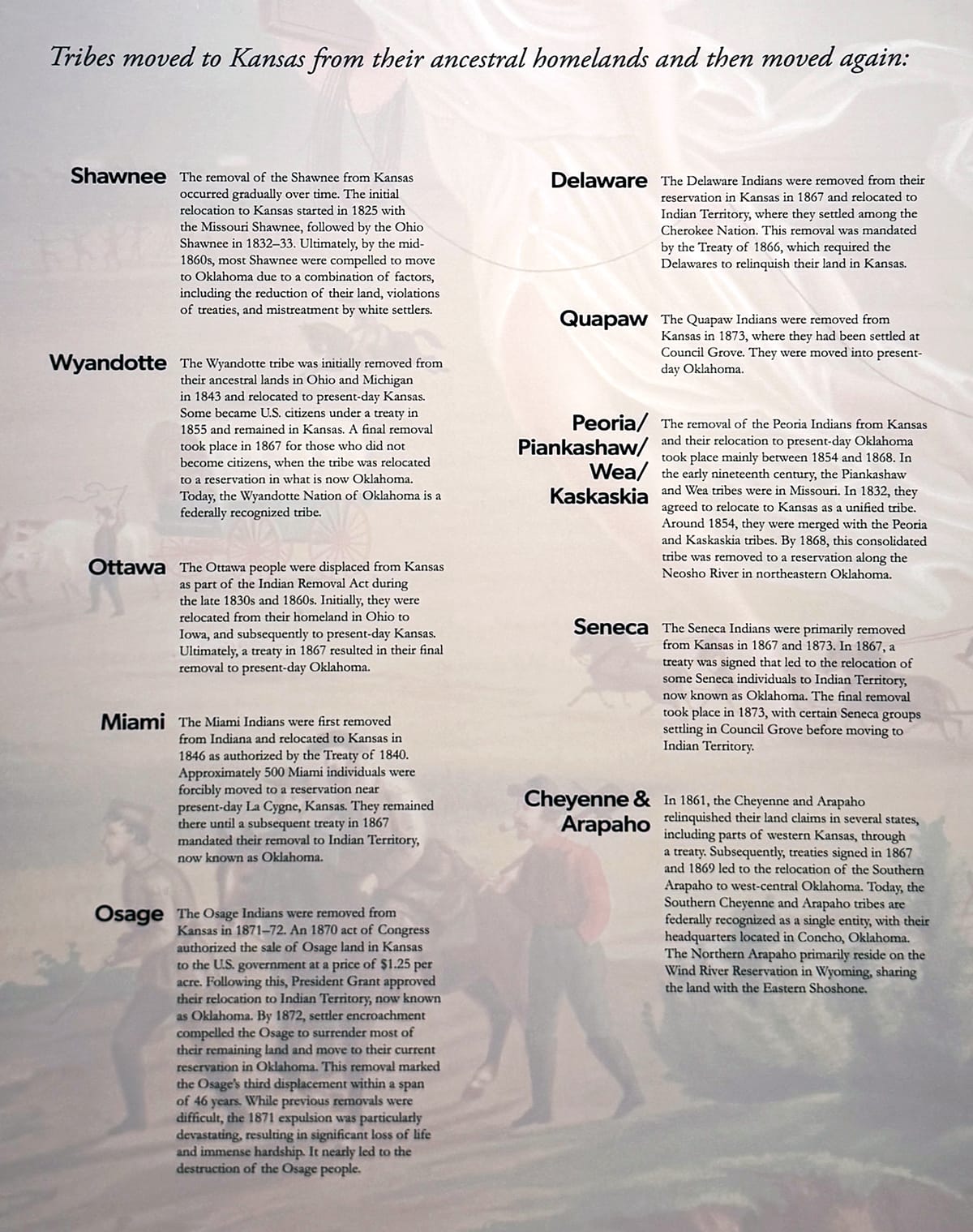

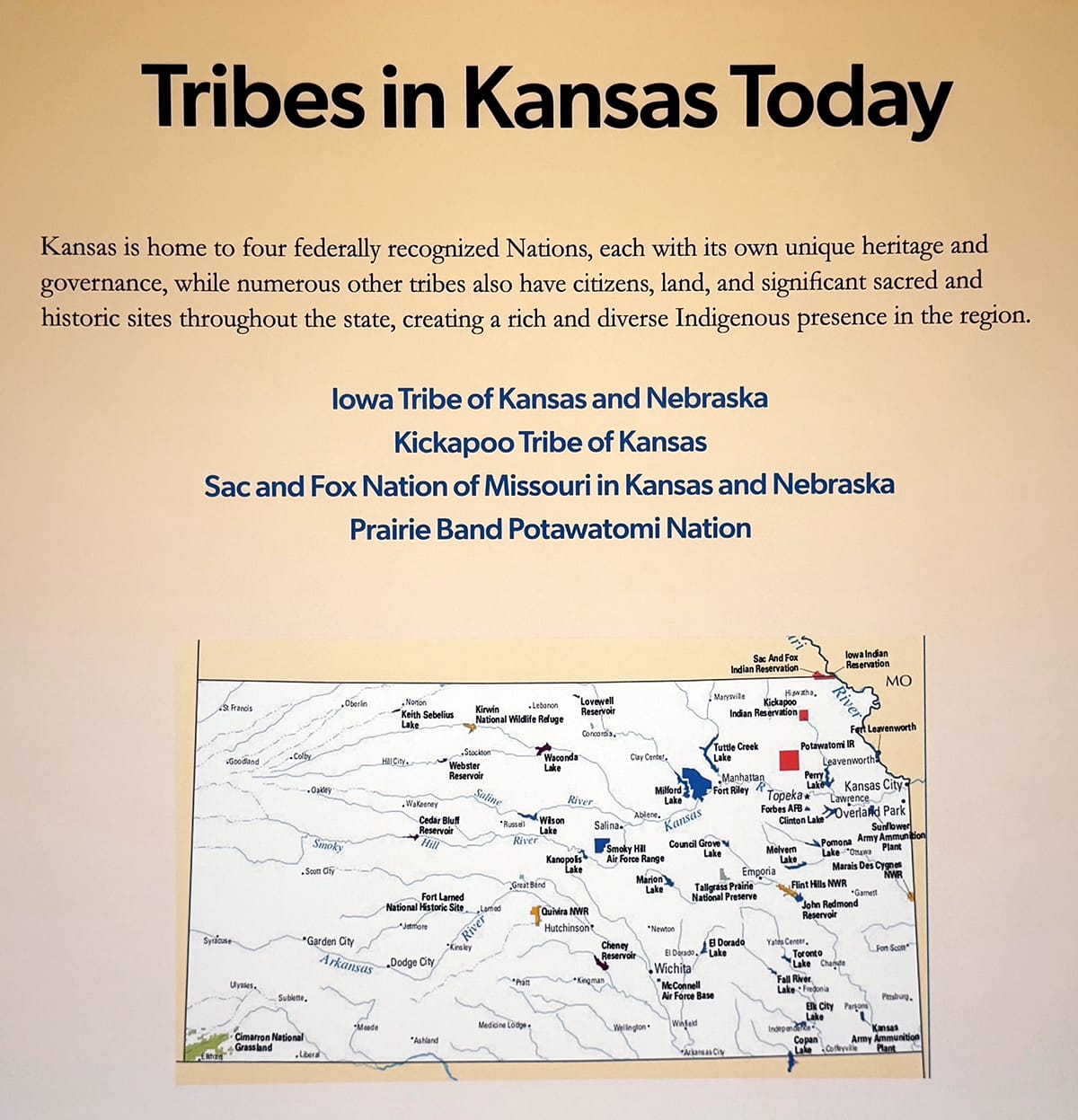

“DoPiKa,” derived from the Indigenous origin of “Topeka,” is not merely a linguistic nod — it’s a conceptual anchor. Through art, the exhibition resurrects Native voices in a landscape long shaped by erasure and forced removal. This two-part exhibition features informative signs, posters, and other materials detailing tribal histories, treaties, and displacement in the Mulvane’s Study Gallery, while the North Gallery brings the educational component to life through two- and three-dimensional works by Indigenous artists. The strength of the exhibition lies in its ability to convey the long and complex history of Native Americans in Shawnee County not just through facts, but through form, color, texture, and metaphor.

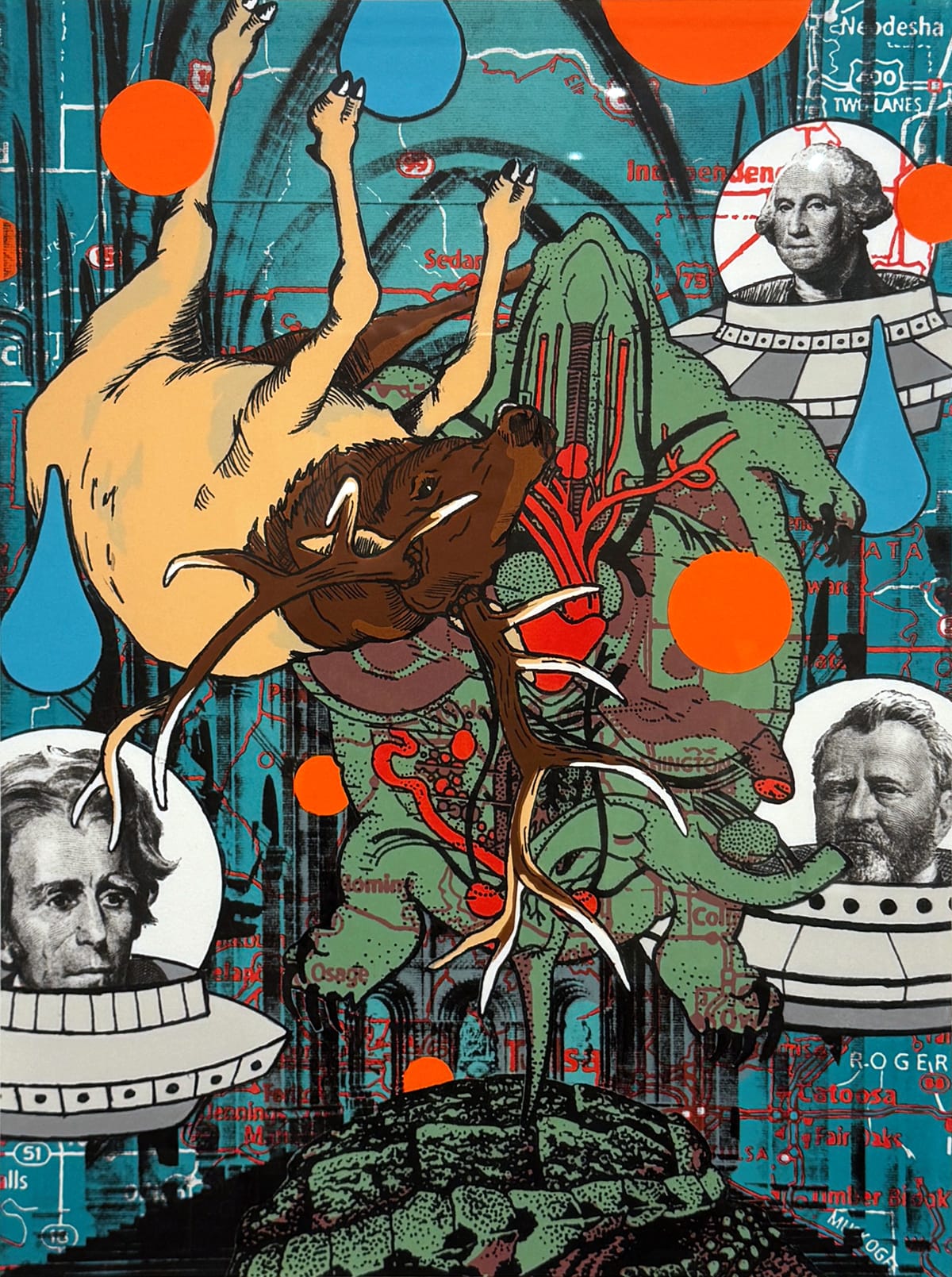

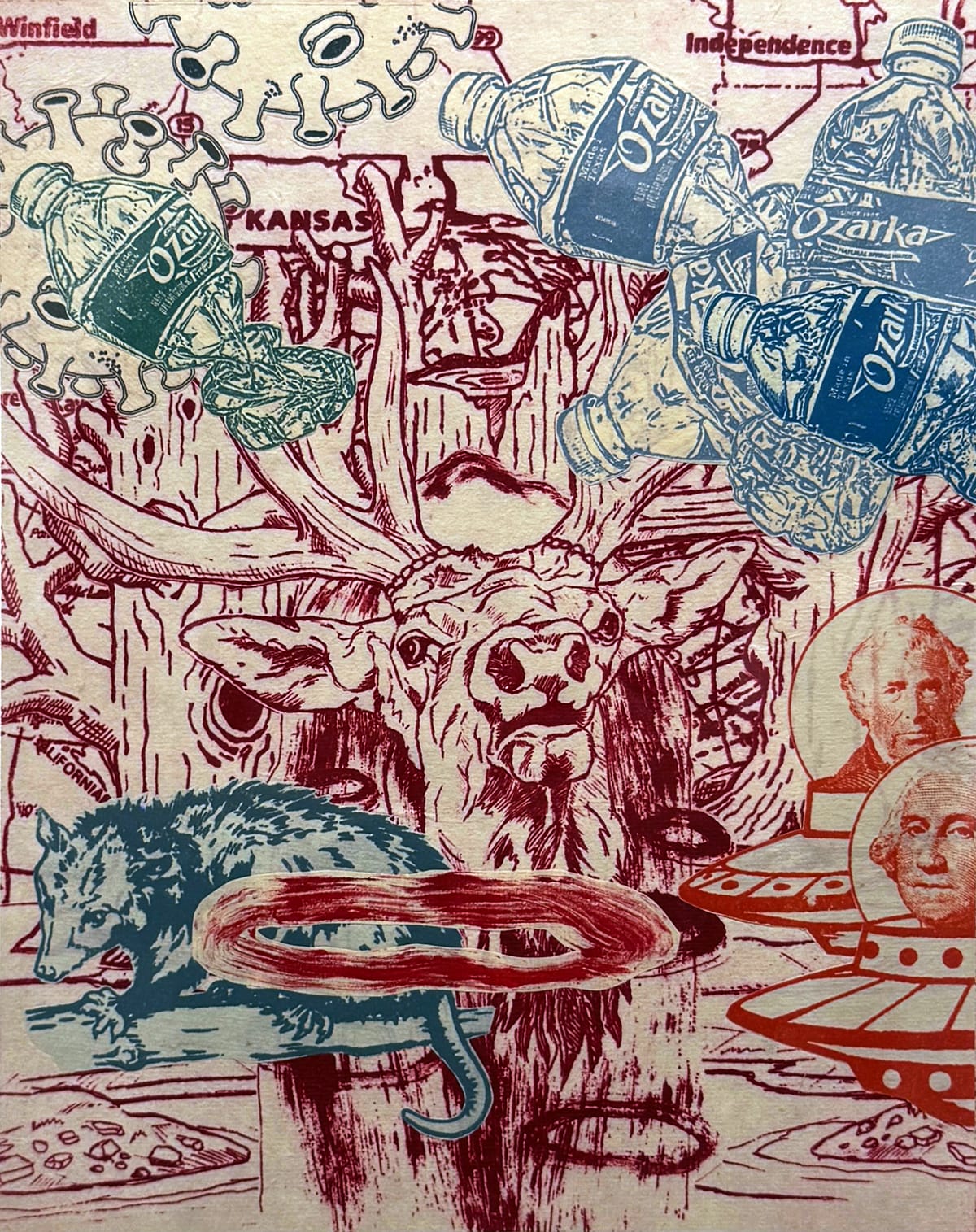

Norman Akers’ symbolically rich works dominate the North Gallery with a series of intricate monoprints and lithographs that both engage and disrupt traditional cartography. Using a visual lexicon that fuses Indigenous iconography with topographical fragments, Akers questions the authority of maps and the stories they have historically told. These are not maps for navigation but for reorientation — psychic, cultural, and environmental.

As Akers says in his artist statement, “Placing (imagery) intrigues me, as it becomes a metaphor for redefining place. The deconstruction of historical images such as maps and figures allows the art to engage in a reconstructive dialogue. This dialogue is not complete without the viewer, as it is meant to engage them in a post-colonial conversation about the place.” Examining the layering and intersection of images, the viewer may interpret the background position of the maps as a symbol of how man-made divisions are imposed upon the landscape and may not speak to our daily experience of living on the land.

In Akers’ more recent pieces that incorporate chine collé, a printmaking process where the artist adheres thin paper to heavy paper, Akers overlays imagery referencing pandemics, climate degradation, and territorial fragmentation. In “Red Elk and Opossum,” the depiction of virus cell structures and discarded plastic bottles floating among animal forms, land boundaries, and founding fathers in UFOs feels less like a warning and more like an invitation to reckon. What does it mean to belong to a place that has been altered, renamed, or nearly erased by “alien” forces?

Our free email newsletter is like having a friend who always knows what's happening

Get the scoop on Wichita’s arts & culture scene: events, news, artist opportunities, and more. Free, weekly & worth your while.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Akers notes the importance of connecting history with the context in which we live today in order to say something meaningful about our “place” in the world, asserting, “As an artist, I embrace the past and my cultural history, which is the foundation of my view of the world. However, I believe it is crucial that my art not only draws from the past but also engages with the present, addressing the pressing issues of our time.”

In contrast to Akers’ prints, Sydney Pursel’s work engages with cultural memory through three-dimensional forms. Her “Rainbow Star Quilt Wearable,” draped over a mannequin, evokes the legacy of boarding schools where Native children were taught European domestic arts — quilting among them — as a tool of assimilation. But in a show of resilience and ingenuity, Native women reclaimed quilting as a space for cultural expression, embedding tribal motifs and symbolism into their patterns. Pursel’s quilt stands as both a memorial and a declaration: a representation of Indigenous endurance repurposing tools of oppression into vessels of identity.

Pursel’s second piece, a whimsical yet pointed installation titled “ReWilding ‘Seed Bomb’ Machine,” furthers this theme of reclamation. Here, she repurposes vintage gumball machines to distribute wildflower and milkweed seed bombs — small clusters of native plant seeds embedded in clay and soil. For a quarter, visitors can take one home and participate in rewilding efforts. The gesture may seem small, but it carries weight. Rewilding, in this context, is not just ecological — it’s epistemological. It’s a way of thinking and relating differently to the land, one rooted in Indigenous stewardship and reciprocal care.

Sydney Pursel (Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska), "ReWilding "Seed Bomb" Machiene", 2019, gumball machiene, red clay, compost, wildflower and milkweed seeds. Photo by Abby Bayani-Heitzman for The SHOUT.

That viewers are encouraged to participate makes this not just an artwork but a quiet call to action. The sign next to the piece reads, “Pursel created this work to address the loss of natural habitats for pollinators in the Midwest. Industrial farming and urbanization have changed the landscape, destroying the natural resources that bees, birds, and butterflies depend on. Planting wildflowers and milkweed can help support these vulnerable populations.” This piece reminds viewers that we are all responsible for protecting our environment and that, because the ecosystem is interconnected, we can become just as vulnerable as milkweed and wildflowers.

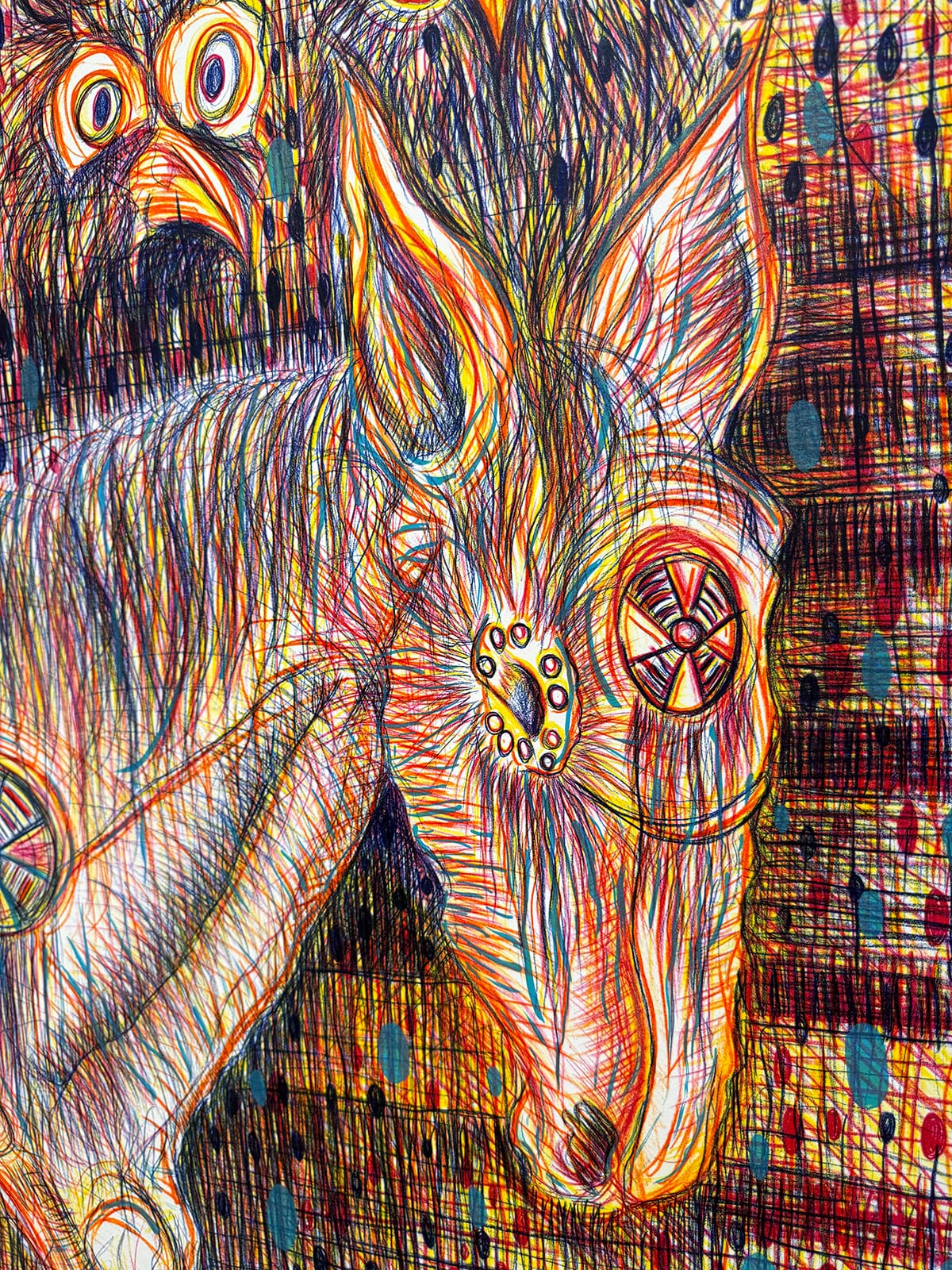

The exhibition’s depth is further enriched by complementary works from the Mulvane’s collection and local artists, which resonate with the themes raised by Akers and Pursel. Reuben IronHorse-Kent’s painting “Prime” reimagines the Trickster figure — so central to many Native storytelling traditions — as a powerful contemporary archetype. Rendered with energy and defiance, the Trickster becomes a cipher for resilience, a visual shout of “Still Here” in the face of centuries of attempted erasure.

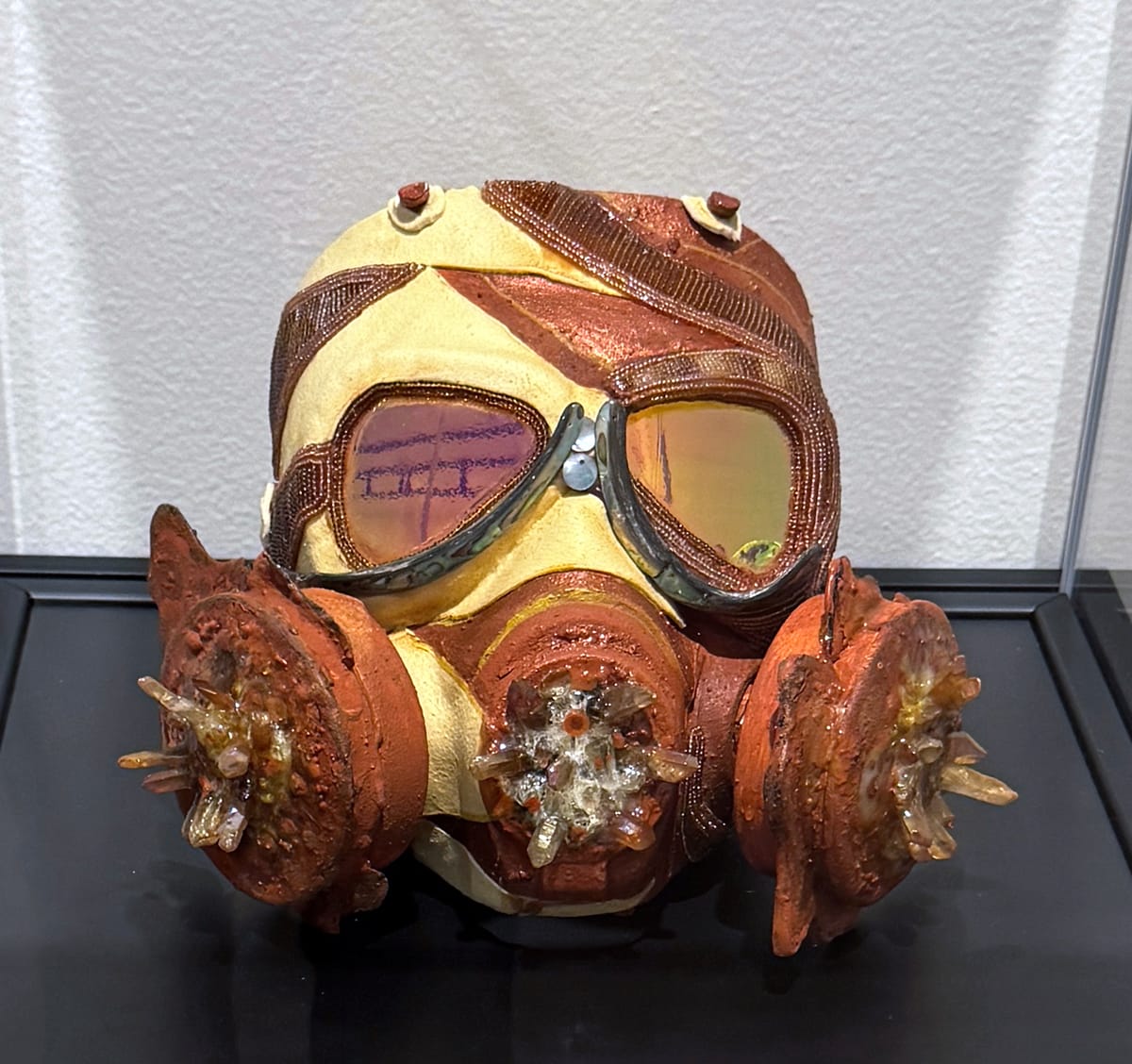

Mona Cliff’s embellished gas mask, by contrast, transports us into speculative territory. In her artist statement, Cliff says, “Generational knowledge connects me to my past, helping me find meaning in my presence as I look towards the future generations.” Her imagined future artifact — a 20th-century gas mask adorned with beadwork, quartz, and shell — blurs the boundary between medicine, spirituality, and survival. It’s a haunting vision: a kind of ceremonial regalia from a post-apocalyptic future where the past must be pieced together from fragments. The gas mask, normally a symbol of toxicity and fear, is transfigured into something sacred — both protective and prophetic.

While the historical research component of “DoPiKa: Reinstate” is thoughtfully presented through wall texts and archival imagery, it wisely steps back to let the art lead. The educational materials contextualize rather than dictate, offering viewers tools for deeper understanding without prescribing a singular interpretation. This curatorial restraint allows the works to breathe and speak on their own terms.

Rather than defining the works, the educational materials in "DoPiKa: Reinstate" situate the displayed artwork within a Native past and present. Photo by Abby Bayani-Heitzman for The SHOUT.

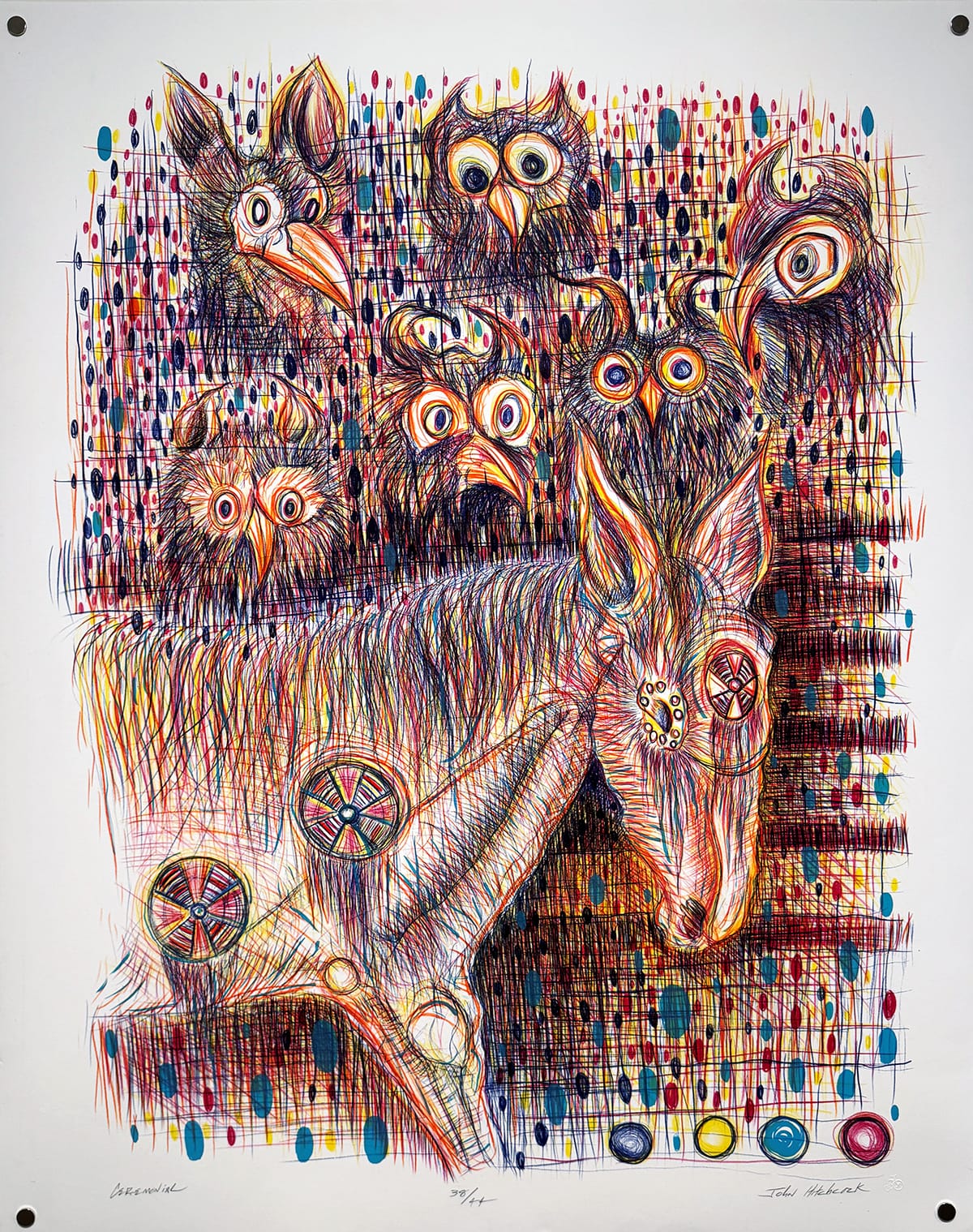

And speak they do. What unites the various works in “DoPiKa: Reinstate” is not a single style or message, but a shared insistence on Indigenous presence — not as a footnote or artifact, but as an active, shaping force. The exhibition refuses nostalgia and resists easy consumption. Instead, it offers complexity, contradiction, and continuity.

John Hitchcock (Kiowa/Comanche/Northern European), "Ceremonial", 2012, lithograph. Photos by Abby Bayani-Heitzman for The SHOUT.

In a cultural moment when land acknowledgments are increasingly common but often perfunctory, “DoPiKa: Reinstate” does something more difficult and more necessary: it reimagines what it means to inhabit land ethically, artistically, and historically. It doesn’t just ask viewers to remember Indigenous histories—it asks them to feel their weight and reckon with their relevance.

Ultimately, “DoPiKa: Reinstate” is not only about reinstating Native narratives when reckoning with the history of the land we inhabit — it is about reinvesting them with agency, visibility, and vitality. Through the powerful, provocative works of Akers, Pursel, and their contemporaries, the exhibition offers a vision of reclamation that is both urgent and enduring.

The Details

“DoPiKa: Reinstate”

July 26-November 15, 2025, Mulvane Art Museum on the Washburn University campus, 1700 S.W. College Ave. in Topeka, Kansas

The Mulvane Art Museum is located on the north end of Washburn University campus at the corner of 17th Street and Jewell Avenue. Free parking is available west of the museum entrance. A wheelchair-accessible entrance is located on the east side of the museum through the Garvey Fine Arts Center.

“DoPiKa: Reinstate” is installed in the Main Level Galleries at the Mulvane Art Museum. The museum is open from noon-7 p.m. Tuesdays, noon-5 p.m. Wednesday-Friday, and noon-4 p.m. Sundays. Admission is free.

Learn more about "DoPiKa: Reinstate."

Abby Bayani-Heitzman is a Filipino American writer born and raised in Northeast Kansas, where she continues to live and work. She received her Master of Arts in English from Wichita State and participated in the second cohort of the Kansas Arts Commission’s Critical Writing Initiative. Since 2021, she has published the fanzine Played Out, which focuses on music and subculture in Kansas.

❋ Derby man has the kind of voice that turns heads — and chairs

❋ Socializing while sober: how some Wichitans are cultivating alcohol-free communities

❋ As a small creative business closes, the owner mourns

❋ Painting through it: Autumn Noire on 20 years of making art

❋ How a guy from Wichita resurrected 'Dawn of the Dead'

❋ Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections

Support Kansas arts writing

The SHOUT is a Wichita-based independent newsroom focused on artists living and working in Kansas. We're partly supported by the generosity of our readers, and every dollar we receive goes directly into the pocket of a contributing writer, editor, or photographer. Click here to support our work with a tax-deductible donation.