Cultural/curatorial transmissions: “Bold Women” at the Spencer Museum of Art

On the campus of the University of Kansas in Lawrence, art across generations reveals the past as present. "Bold Women" is on view through July 6.

This was my apprehension: that the Spencer Museum of Art’s current exhibition, “Bold Women,” would amount to continued litigation for women’s place in the patriarchal canon. Considering the current landscape, I would understand. Fortunately — and refreshingly — the show is an expansive, full-throated testament to the boldness of women’s artistic voices and the creative conversations they have always initiated.

“Bold Women” is a large-scale exhibition that demonstrates fearlessness in the face of institutional norms and determination in imagining resilient futures. It posits womanhood as a varied but distinct experience, one that works through transmissions. Across generations and around the globe, women challenge expectations, artistic mediums, unimaginative societies, and gender norms. They transmit their defiance to each other and to their descendants — this is how a bolder world comes about. The show is a revelation. It’s a broad, contemporary, and expansive look at the artistic and innovative lives that women share.

Installation views from "Bold Women" at the Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas. Photos by Ryan Waggoner and courtesy of the Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas.

The exhibition is divided curatorially into four sections: Portrayal/Resistance, Collective Preservation/Liberation, Wisdom/Knowledge-Keeping, and Nature/Erasure. At the entrance, viewers are greeted by a large-scale ink drawing of chains by Lawrence artist Hong Chun Zhang. The breathtaking work, which the museum commissioned for “Bold Women,” sets the tone.

Amid the large works and vibrant colors, however, a piece that drew me in close was the small (approximately 2- x 3-inch) photo by Claude Cahun, “untitled (self-portrait),” from around 1927. A silver gelatin photograph, the image depicts Cahun in a defiant pose with spread knees and leather cuffs, making unnerving eye contact with the camera/viewer. Her shirt appears to depict nipples with the freedom that men have in being topless. Cahun consistently explored the boundaries of both femininity and masculinity in her work and life. In her 1930 book “Disavowals” she wrote: “Shuffle the cards. Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” (There is debate over the pronouns Cahun would use today, but throughout the artist’s life she used the she/her pronouns that were available to her.)

Cahun and her partner Marcel Moore were writers and activists who used play and creativity to subvert gender norms and wage resistance against the Nazi regime. This is the kind of historical work I find redemptive. Women have always been artists, have always been subversive and daring, and have always explored and transgressed the boundaries set upon us. Our absence in the art history books is not because we were not doing the work. It is not even that we weren’t allowed to do it. Cahun is proof of that.

Subscribe to our free email newsletters

Stay in the know about Wichita's arts and culture scene with our Sunday news digest and Thursday events rundown.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

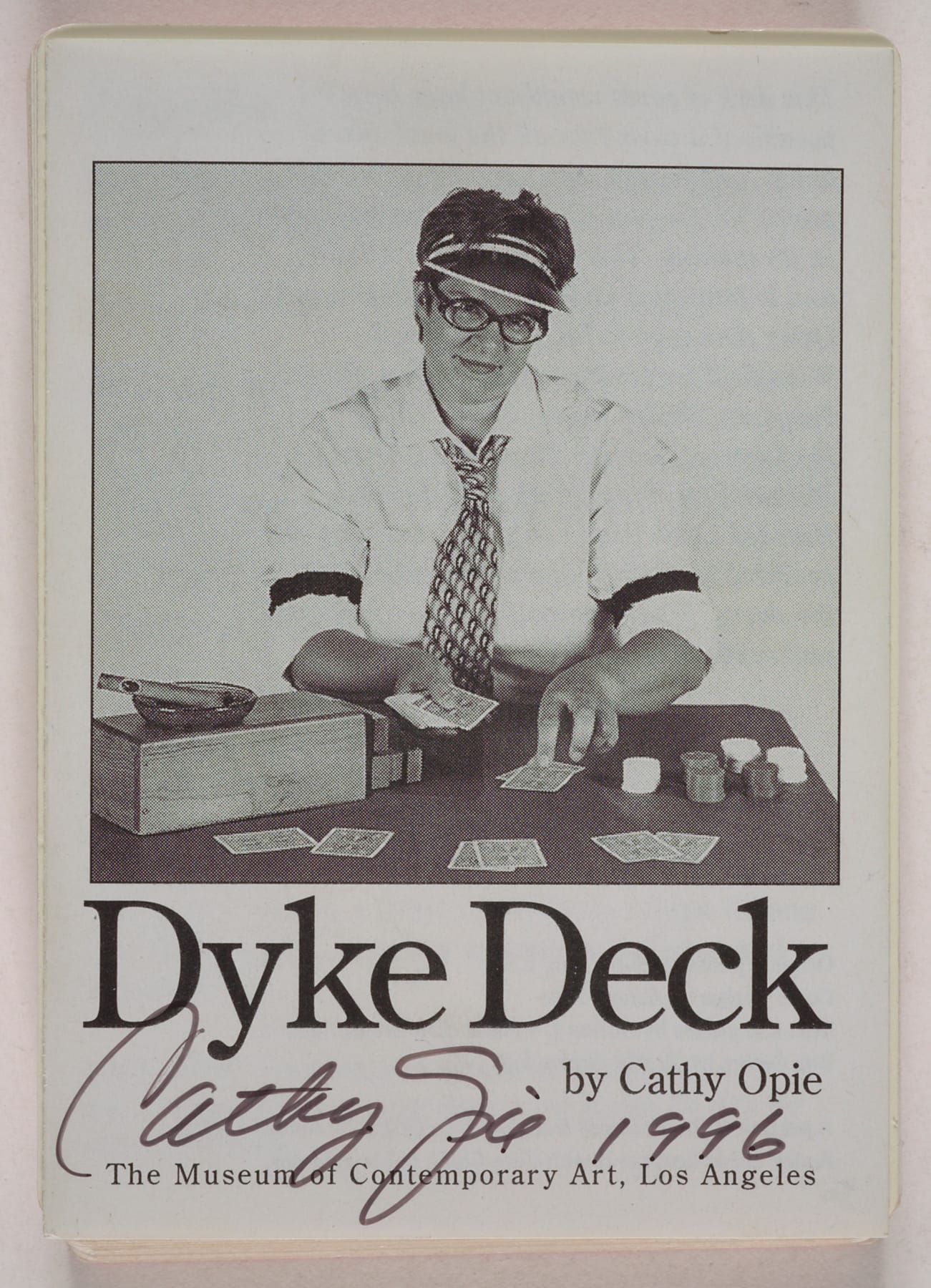

Yet despite being outside the canon, transmissions occurred. Cahun’s 1927 image could be included in Catherine Opie’s 1996 “Dyke Deck,” created nearly 70 years later. Opie’s work depicts black-and-white images of gender nonconforming lesbians. In the placard Opie states, “I try to present people with an extreme amount of dignity. They’re always going to be stared at, but I try and make the portraits stare back.” Staring back presents a challenge to the viewer.

This defiance is also seen in Ingrid Pollard’s 2018 manipulated photo “Emancipation Day Celebration,” in which she uses an image of stoic celebrants in Jamaica in the 1890s. Here, women look at the photographer, proud, strong, and dignified.

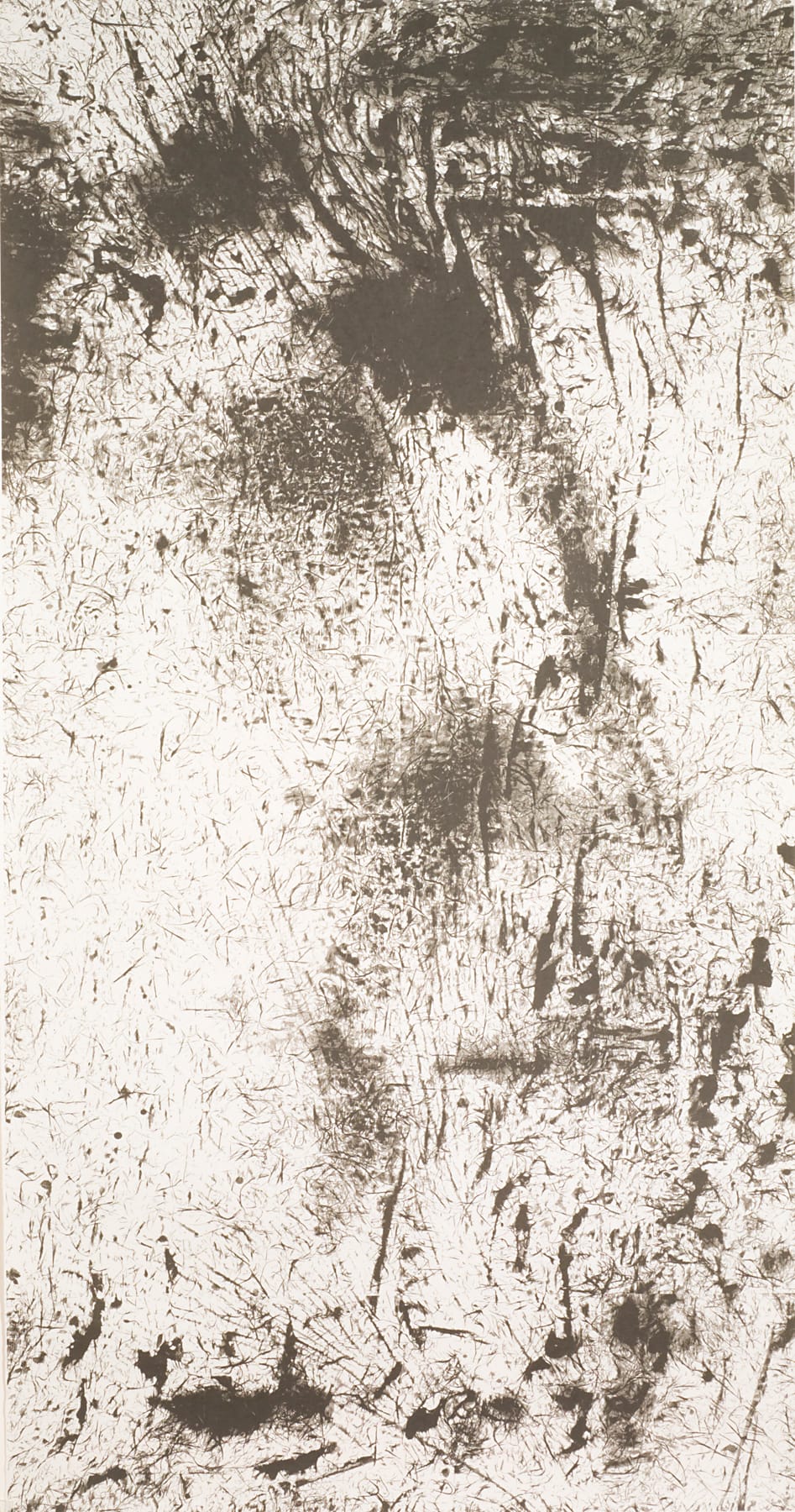

More abstractly, Koo Kyung Sook’s self-portrait “Markings No. 7-3” (2007) is an image the artist created by wrapping herself in faux fur that was soaked in photo chemicals. With the chemicals on her skin, she then placed her body on photosensitive paper. The camera-less photo is a fascinating gathering of explosive line and movement, reminiscent of Erin Wiersma’s “Konza Prairie” burn images or Cai Guo-Qiang’s gunpowder works.

Under masterful curation by Susan Earle (with advisors Kimberli Gant and Wanda Nanibush), Sook’s self-portrait is in conversation with nearby pieces by Zhang and Shelley Niro. Zhang’s Chinese-style ink drawing “Twister #2” (2012) and Niro’s inkjet print “Raven at Night” (2022) also employ line and movement to imagine transformation and change. In an exhibition as large as “Bold Women,” curation and connection are necessary to keep the works from overwhelming the viewer.

From left: Hong Chun Zhang, "Twister #2," 2012, charcoal, paper, wood; Shelley Niro, "Raven at Night," 2022, inkjet print, paper. Images courtesy of the Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas.

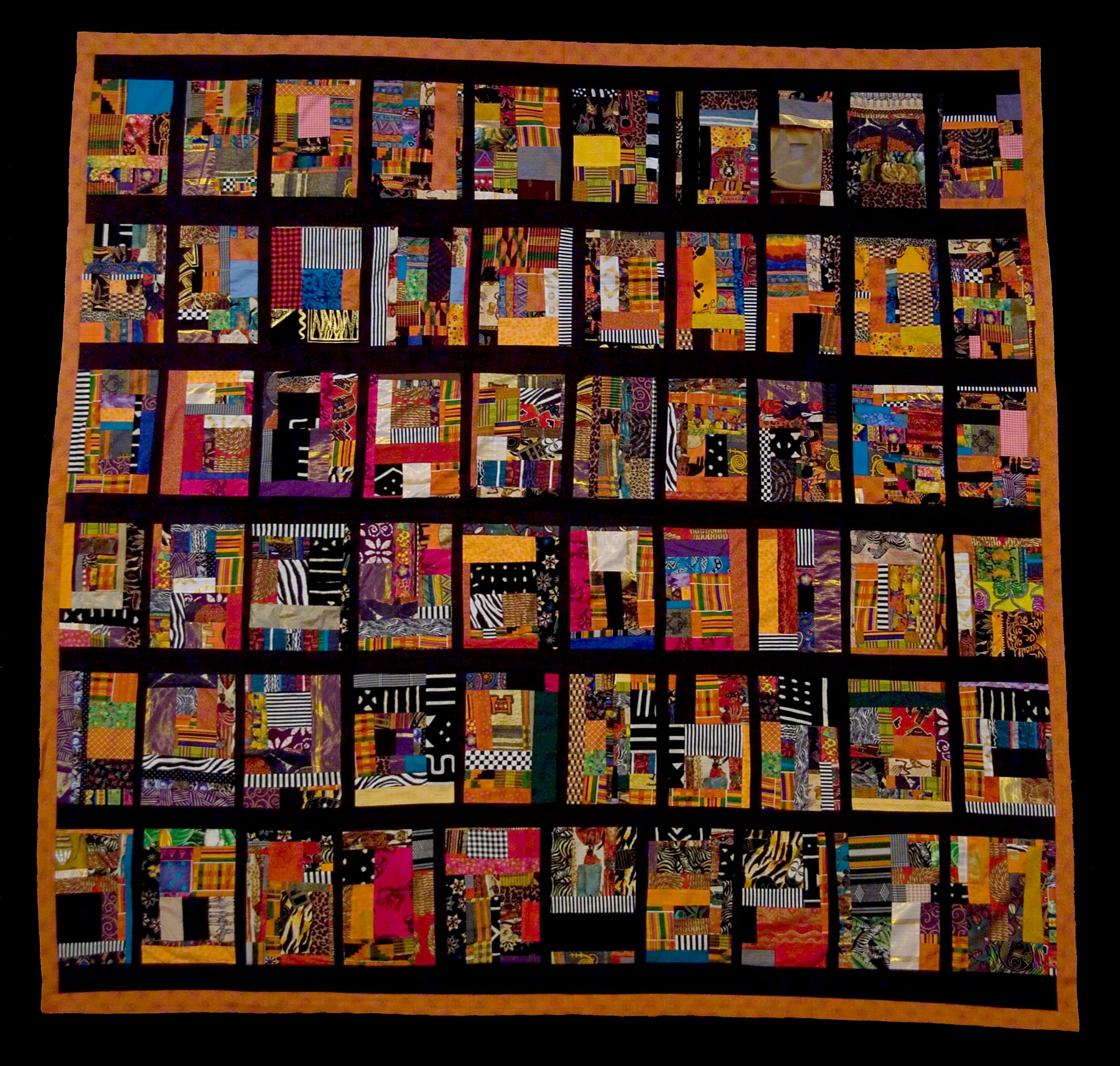

Textile arts are often the foundation of female artistic practice and cultural transmission from one generation to the next, so quilts are prominent throughout the show. Again, a curatorial conversation is at play in these pieces. Renée Fleuranges-Valdes depicts an Afro-futurist warrior, “Akofena: Defender of the Land” (2022), in an assemblage of traditional and unexpected materials, including crystals. In the Wisdom/Knowledge-Keeping section, in Sonié Joi Thompson-Ruffin’s “East Side Quilt” (2004-2005) the artist also utilizes quilting to tell the story of her Joplin, Missouri neighborhood.

Renée Fleuranges-Valdes, "Akofena: Defender of the Land," 2022, cotton, silk, thread, yarn, Swarovski crystals, cotton fiber, piecing, appliqué, embroidering; Sonié Joi Thompson-Ruffin, "East Side quilt," 2004–2005, cotton, kente, piecing. Images courtesy of the Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas.

Ke-Sook Lee’s “Awakening in Her Garden 3” (2001), made of nontraditional materials such as clay, rice paper, and thread, tells domestic stories in quilt-like squares. Like Louise Bourgeois, Lee was inspired by the industriousness of spiders, which she observed in her garden and related to through her many identities as a woman, a mother, a gardener, and an artist.

Academic art museums can be tiring — instructive but also didactic, with shows that lead the viewer on a leash to the expert conclusions. “Bold Women” triumphs in respecting the viewer's ability to connect and contextualize in personal and unique ways. This, to me, is the most exciting kind of art experience: when an exhibition gives me context but not meaning; when my worldview can be shifted and expanded in directions I did not expect. Like women, the museum should be a bold but wild space.

Installation views from "Bold Women" at the Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas. Photos by Ryan Waggoner and courtesy of the Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas.

The Details

"Bold Women"

February 18-July 6, 2025 at the Spencer Museum of Art, 1301 Mississippi St., in Lawrence, Kansas

A virtual version of the exhibition is available and includes additional interviews, podcasts, and learning opportunities.

The Spencer Museum is open from 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Friday and noon-5 p.m. Saturday-Sunday. Admission is free.

Leslie VonHolten is an arts and environmental writer who lives in Lawrence. She is co-editor, with Thomas Fox Averill, of "Kansas Matters: 21st-century Writers on the Sunflower State," which will be published in fall 2025.

Support Kansas arts writing!

The SHOUT is a Wichita-based independent newsroom focused on artists living and working in Kansas. We're partly supported by the generosity of our readers, and every dollar we receive goes directly into the pocket of a contributing writer, editor, or photographer. Click here to support our work with a tax-deductible donation.

⊛ What is 'percent for art?' About the public art funding program that Wichita art advocates don't want to lose

⊛ How a guy from Wichita resurrected 'Dawn of the Dead'

⊛ Painting through it: Autumn Noire on 20 years of making art

⊛ 'You don't have to give up': Clark Britton on making art into his 90s

The latest from the SHOUT

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTSam Jack

The SHOUTSam Jack

The SHOUTTeri Mott

The SHOUTTeri Mott

The SHOUTShelly Walston

The SHOUTShelly Walston