Giving God a show: Leisure as prayer in 'Safer Waters'

In an exhibition at the Wichita Art Museum, Stephen Towns invokes a higher power who affirms the dignity of Black Americans.

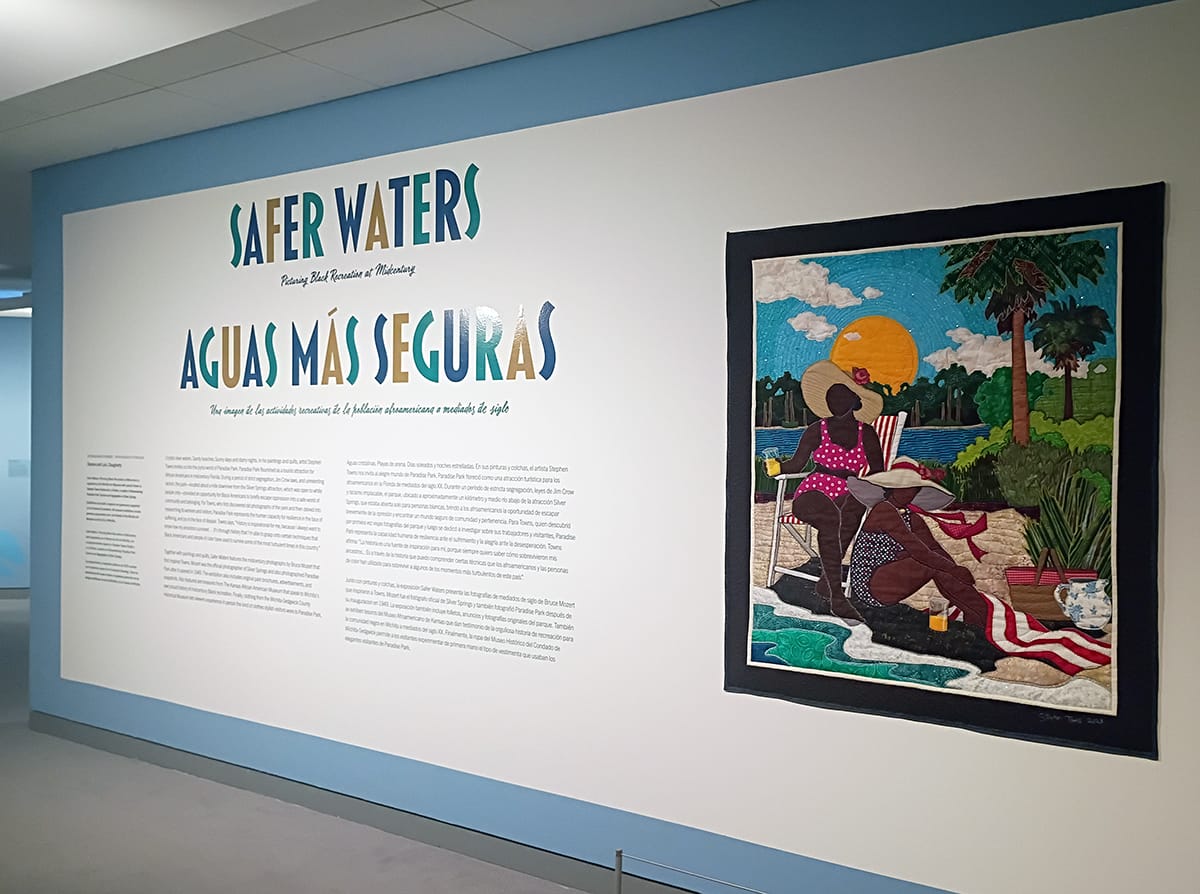

The critical corpus surrounding the work of artist Stephen Towns relies primarily on the concept of resilience. From the informational texts at the numerous museums that have collected his work to the reviews of his many exhibitions, critics inevitably hone in on his theme of Black Americans refusing to accept the image of themselves reflected back at them by white supremacy. Yet Towns' current exhibition at the Wichita Art Museum is not so easily reduced. Titled "Safer Waters: Picturing Black Recreation at Midcentury," the show explores something deeply theological and existential. It is something a bit underserved by the word recreation and better described as leisure.

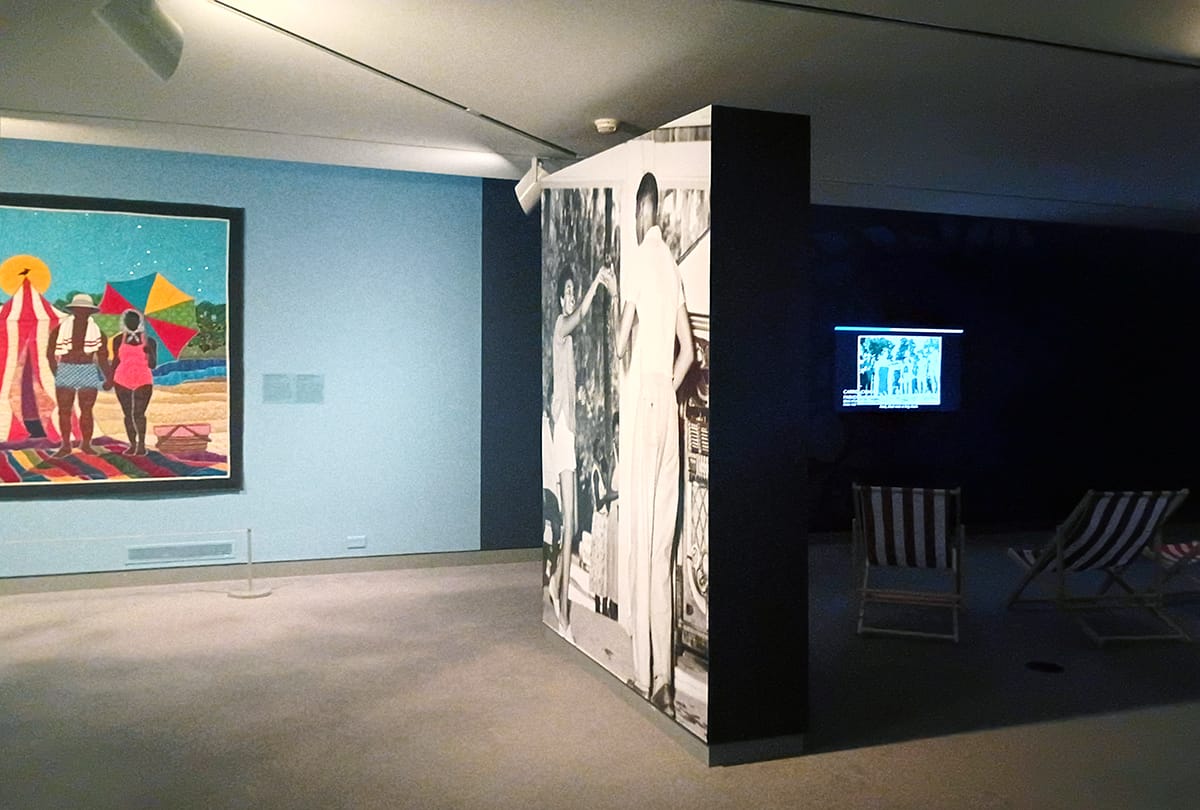

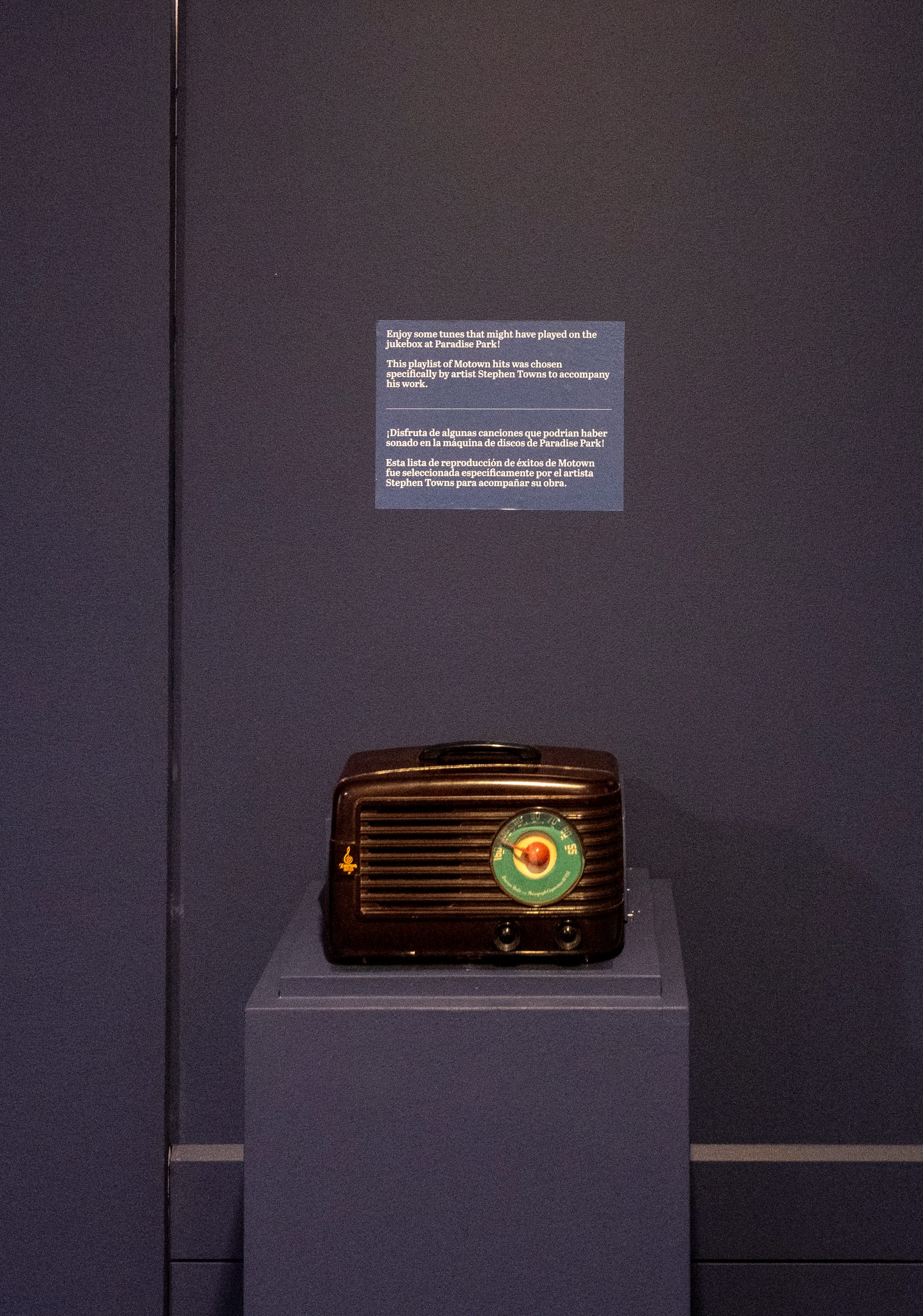

"Safer Waters" revolves around the Florida resort Paradise Park, which during the Jim Crow era of segregation functioned as the Black alternative to the whites-only Silver Springs, now a state park. Both attractions were based around an apparently stunning group of artesian springs along the Silver River in northern Florida. At WAM, Towns' collections of paintings and quilts are placed in conversation with the photographs of Bruce Mozert, who documented the slice of paradise made by and for "colored people," as its sign read during its 1949-1969 tenure. Clothing and other artifacts from both The Kansas African American Museum and the Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum, as well as a short documentary film featuring Towns and former Paradise Park patrons, complete the exhibition.

I call the show theological because Towns himself has claimed that dimension for his work. A prior project entitled "Stephen Towns: A Migration" featured a series of paintings in which he drew the titles of all six works from the 30th Psalm. And in "Safer Waters," Towns states plainly that his use of gold leaf represents "God, the universe, the spirit that surrounds everyone." The interpretive key to "Safer Waters" is the fact that such a spirit does not merely surround, it keeps a record. The "resilience" of Towns' subjects is not merely a subjective self-assertion of dignity in the face of racism. It is a recorded fact, something marked by an objective watcher, the old-fashioned word for whom is "God." It matters that someone else — a someone else beyond error — affirms the dignity of these Black Americans deemed unfit for white spaces. This someone else remembers what the white system of denigration seems so intent on denying.

Our free email newsletter is like having a friend who always knows what's happening

Get the scoop on Wichita’s arts & culture scene: events, news, artist opportunities, and more. Free, weekly & worth your while.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

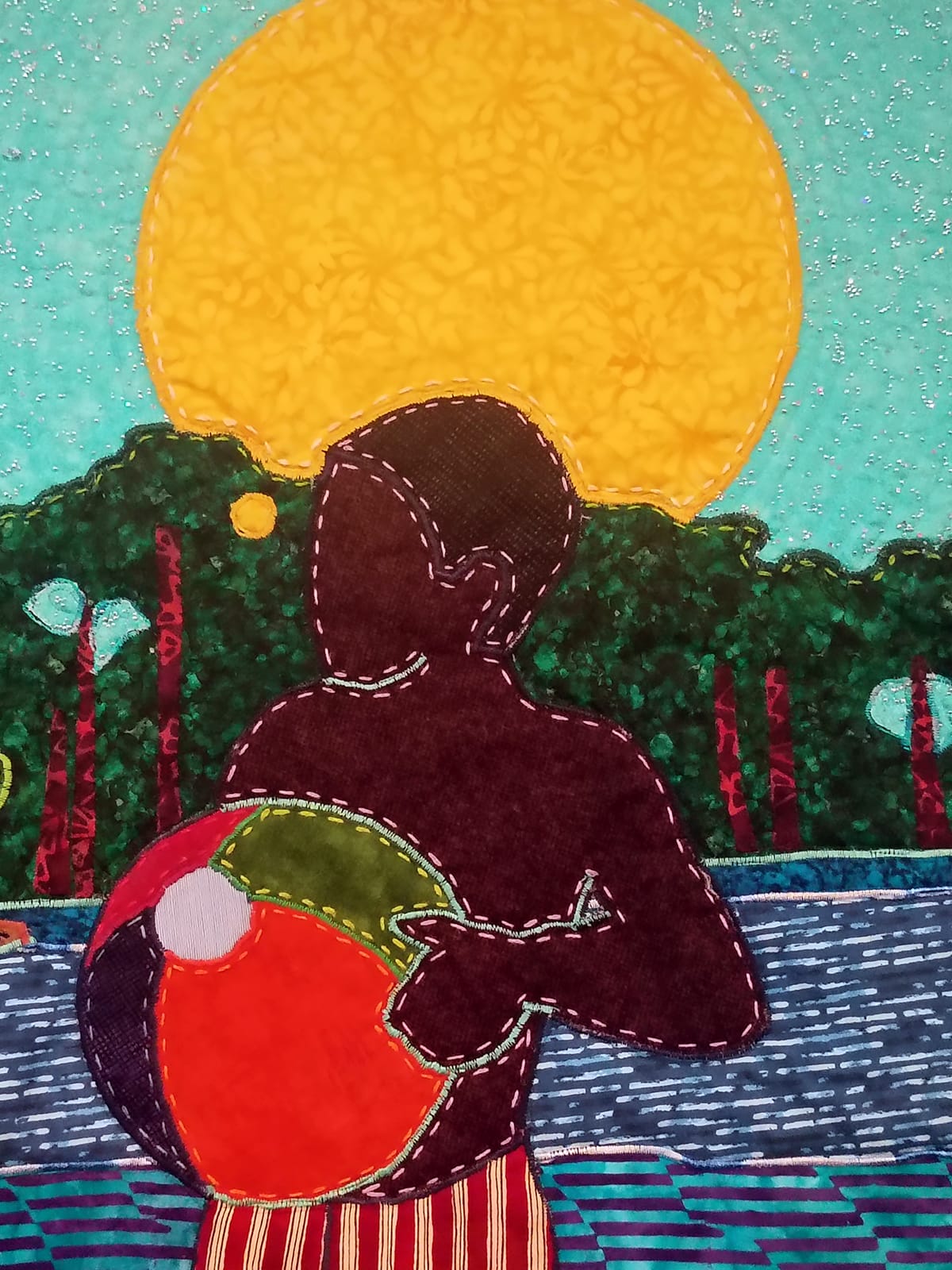

Take, for instance, the quilted work "Luncheon on the Sand." A faceless couple in beachwear confront the viewer and behind them, perched atop a red-and-white striped tent, appears a bird that is backlit by an egg-yolk of a sun. This bird is God. Or, as Towns puts it, a "watcher." A watcher of this couple, "a truth teller, able to tell of this love that they have for each other." In many ways, "Safer Waters" is a prayer, an assured but needy one that says "You saw this, right? You saw what we did, how we kept ourselves human?" The answer in paint and fiber and butterflies and gold and sand and sun and moonshine is "Yes beloved, I saw it all, and I've kept it safe. No one will ever be able to take it away." Towns' every stroke and stitch insist that this happened, this happened, this happened. A manifesto entwined with the show's second refrain: we are, we are, we are.

A whole painting, in fact, is called "When We Were." The horizon is entirely coated with gold leaf, and three foregrounded boys once again face us head-on, surrounded by kites, a tent, and a basketball. In the middle-ground is a river on which glides a white boat. In the left corner is a butterfly. Towns freights butterflies with the we-are-ness of his subjects. He likes that they migrate and that, while they tend to drop dead, the group as whole ultimately makes it where it's going. What, then, to make of the butterfly — a disconcerting mix of memento mori and token of hope — floating about three children in a work named "When We Were." Perhaps at least one of them no longer is. But the gold leaf — God — saw it all: the gone-boy's laughter, his awe, his mirth, his delight. John Ruskin reminds us that we have a religious duty to delight — something similar to leisure, whereby we spend attention and time on something which produces nothing, which we enjoy not for its own sake but as an exercise in the sacred right of humanity to exist without use. These boys fulfilled their duty.

Towns pays attention to the evil vectors of hatred and how they fall unevenly on our bodies. In the quilt "Looking for Lorraine," an homage to Black queer women, and a titular allusion to the Black gay cinematic meditation "Looking for Langston" (1981) by Sir Isaac Julien, we see a group of women sprawled about on the beach. They are relaxed, at places entwined, they have flowers in their hair, and they read serious magazines containing profiles of Lorraine Hansberry. These are women who are not thinking about how they're being perceived. These are women living now as opposed to later. Hansberry's play "A Raisin in the Sun" was titled after a line in Langston Hughes' poem "Harlem":

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?"

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

The answer is immaterial, because at Paradise Park dreams were not deferred — they were insisted upon, realized, lived, and, for some, likely lost. But they were not deferred, because being human cannot wait and cannot be denied. Because now is the time for leisure, now is the time to give God a show.

Installation views of the exhibition "Safer Waters: Picturing Black Recreation at Midcentury." Featuring paintings and quilts by artist Stephen Towns, the exhibition is on view in the Ross Ritchie Gallery at the Wichita Art Museum through June 14, 2026. Photos by Jeromiah Taylor for The SHOUT.

Installation views"Safer Waters: Picturing Black Recreation at Midcentury" with artifacts provided by The Kansas African American Museum and the Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum. Photos courtesy of the Wichita Art Museum.

The Details

"Safer Waters: Picturing Black Recreation at Midcentury"

December 20, 2025-June 14, 2026 in the Ross Ritchie Gallery at the Wichita Art Museum, 1400 W. Museum Boulevard in Wichita

Museum hours are 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Wednesday through Sunday and 10 a.m.-9 p.m. Fridays.

Admission is free and the facility is accessible to people with physical disabilities.

Jeromiah Taylor is a writer from Wichita, Kansas. He is the associate opinion editor at the National Catholic Reporter.

❋ Derby man has the kind of voice that turns heads — and chairs

❋ Socializing while sober: how some Wichitans are cultivating alcohol-free communities

❋ As a small creative business closes, the owner mourns

❋ Painting through it: Autumn Noire on 20 years of making art

❋ How a guy from Wichita resurrected 'Dawn of the Dead'

❋ Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections

Support Kansas arts writing

The SHOUT is a Wichita-based independent newsroom focused on artists living and working in Kansas. We're partly supported by the generosity of our readers, and every dollar we receive goes directly into the pocket of a contributing writer, editor, or photographer. Click here to support our work with a tax-deductible donation.