Material love: 'Kansas Triennial 25/26' at the Beach Museum of Art

Mona Cliff, Mark Cowardin, Poppy DeltaDawn, and Ann Resnick offer "a delicious assortment of media" in an inaugural triennial exhibition at K-State.

After visiting the “Kansas Triennial 25/26” at the Beach Museum of Art, located on the campus of Kansas State University, my initial thought was: I wish I could have installed this show myself. I would have loved to touch all the artworks and experience the feel of the materials in my hands, under my fingertips. The four artists in the exhibition, Mona Cliff, Mark Cowardin, Poppy DeltaDawn, and Ann Resnick, share an interest in exploring the tactile and textural qualities of art while employing a variety of materials: live wood alongside intricate beadwork, delicately burned and layered papers, woven fabrics and baskets, and sculptures combining found objects with smoothly crafted wooden elements. It’s a delicious assortment of media.

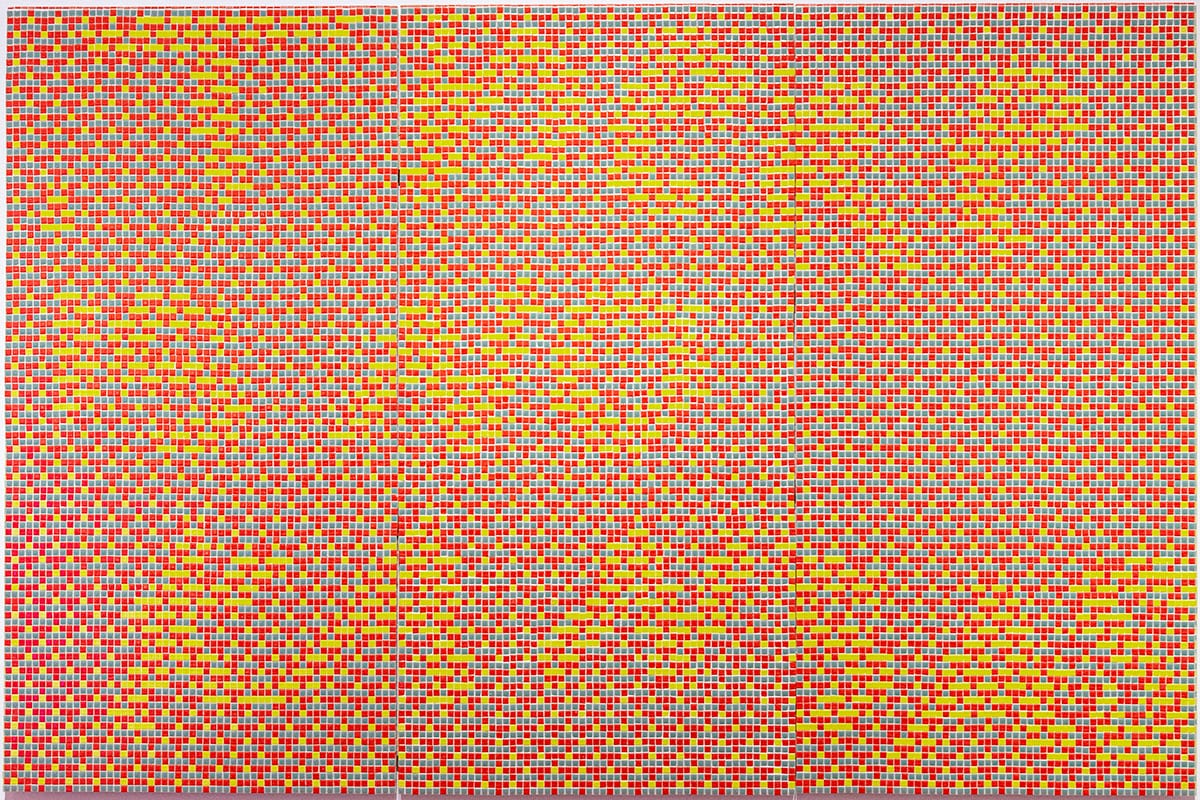

Poppy DeltaDawn, "There is no Kansas," 2024, ceramic tile and grout on panel. Photos courtesy of the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University.

Of course, that assortment also speaks implicitly to the materials left out. I’ve been in this field long enough to recall late-twentieth-century discussions about the so-called death of painting, and then to have seen its insistent revival. And while I don’t consider myself a traditionalist, it surprised me at first that a snapshot of contemporary art in Kansas would include no paintings. Instead, Cliff, Cowardin, DeltaDawn, and Resnick pose big questions and then answer them in whatever media feels most appropriate. Not rejecting painting, nor simply embracing “mixed media” per se, they offer visual statements that communicate a love of materials and process.

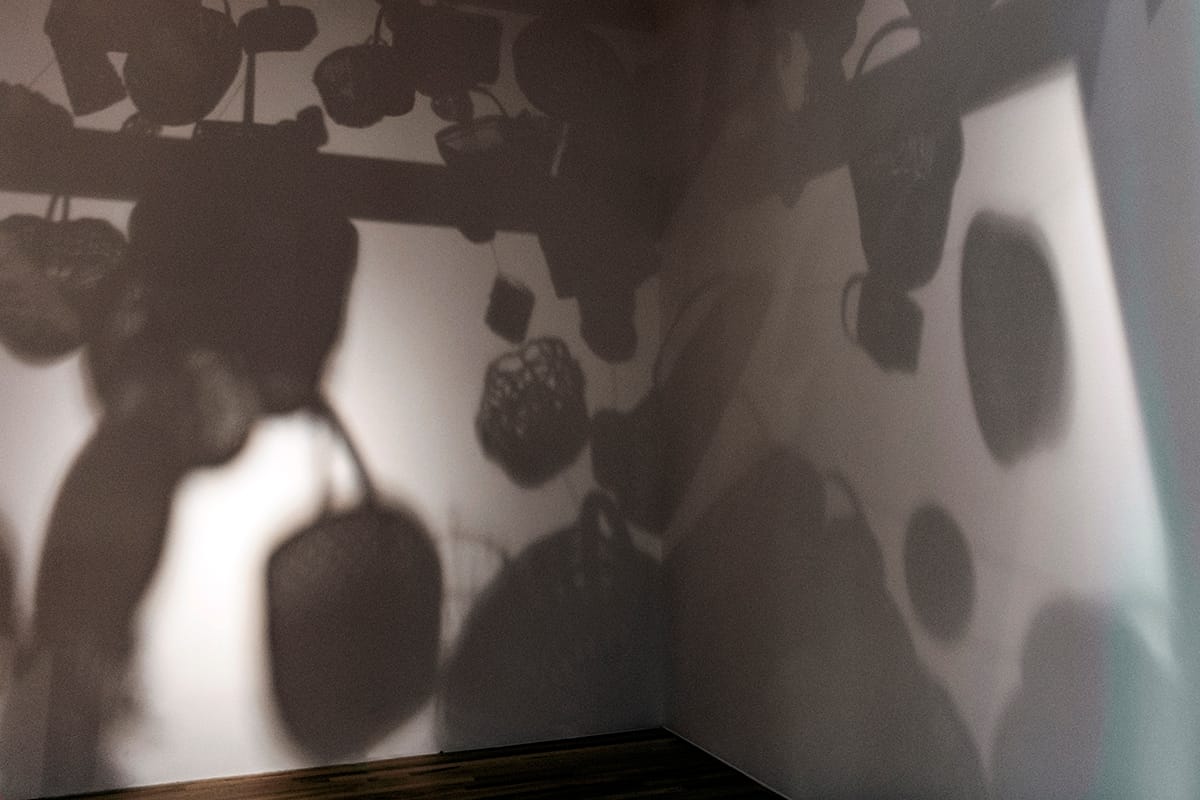

Poppy DeltaDawn, “Woven,” 2025, baskets, cedar, and textile. Photos courtesy of the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University.

Poppy DeltaDawn opens the exhibition with “Woven,” a room-sized installation of weaving — an act that evokes the importance of collective making. Hundreds of woven baskets hang from wooden beams high in the air, in a celebration of traditions shared by many cultures. The artist wove some of the baskets; others she selected, collected, and assembled for this work. Installed together, far out of reach, they create a woven ceiling that casts a spray of dappled light, as if filtered through tree leaves, with their patterned shadows covering the walls.

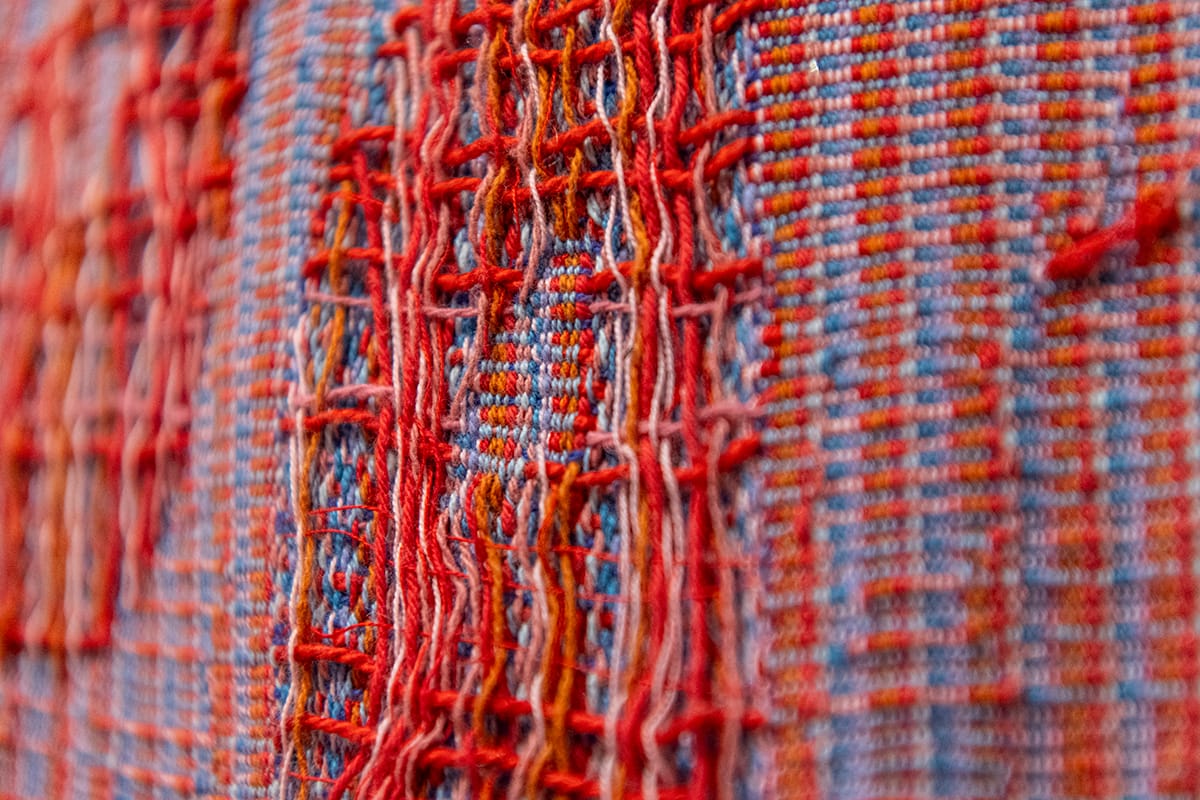

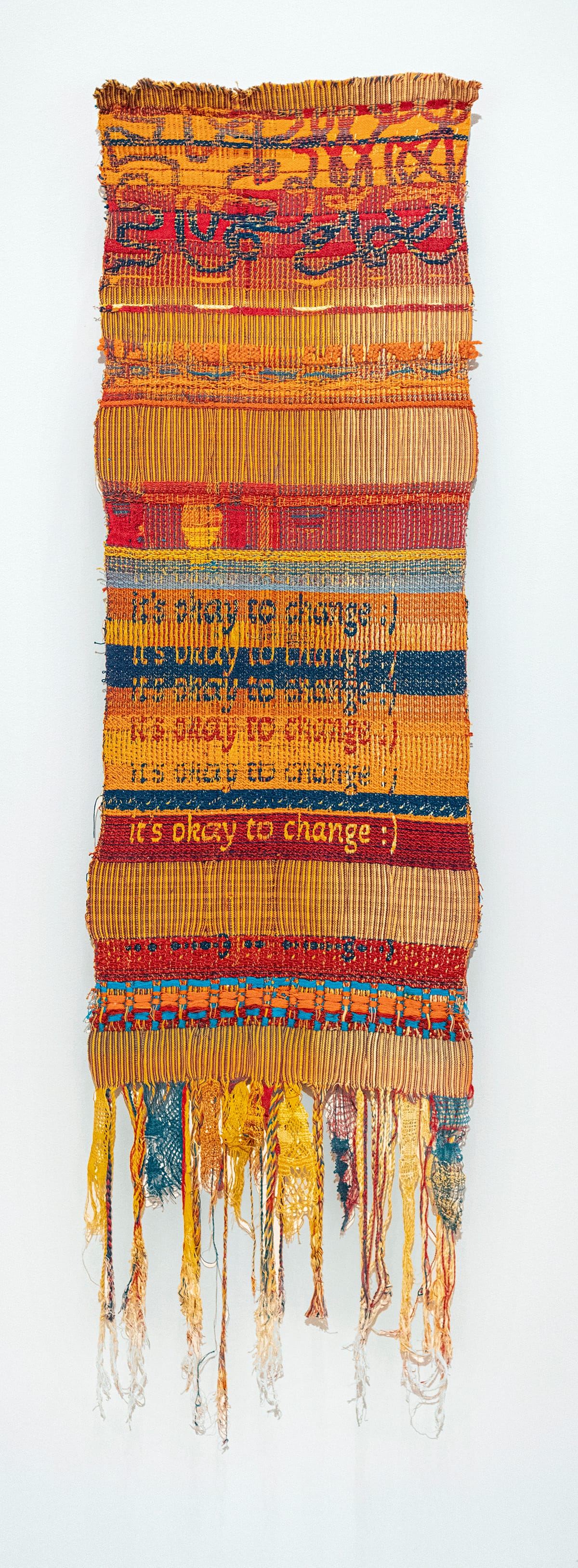

An accompanying woven textile that is closer to eye level, titled “Arachne,” features a prominent spiderweb along with the repeated words: “Let us be free, or die.” The layers of weaving — in the wall hanging, the baskets, and the web — alongside the plural “us” of the artist’s text are references to community, where individuals are woven together in a structure of collective support. Perhaps, too, DeltaDawn calls on us to acknowledge our shared, multi-species interdependence and how the ways in which we choose to care for each other, or not care for each other, either strengthen ties or break them apart. DeltaDawn’s use of woven text throughout the exhibition hints at the precarity of these ties, highlighting phrases such as “Let me be loved” and “it’s okay to change :)."

Poppy DeltaDawn, “Let me be loved,” 2025, handwoven mylar and cotton thread. Photo courtesy of the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University.

Poppy DeltaDawn, “It’s Okay to Change,” 2025, handwoven cotton thread. Photo courtesy of the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University.

Mark Cowardin occupies most of the floor space in the exhibition with his work “Chat Fields,” made up of a collection of sculptural assemblages large and small. For years, Cowardin has explored unusual juxtapositions of natural and human-made materials — for instance, wooden beams joined with fluorescent lights. He also crafts materials so that they mimic the appearance of other things, like slip-cast ceramics that take on the look of brightly colored plastic.

Detail views of Mark Cowardin’s "Chat Fields." Photo courtesy of the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University.

The accompanying label for his piece in the “Kansas Triennial 25/26” show eloquently frames Cowardin’s sculptures as an elegy to environmental extraction, mapping the arrangement of the elements to the mining sites of lead and zinc that surrounded his childhood home. If the sculptures meditate on the devastating impacts wrought by humans’ extraction of natural resources, we should not discount the whimsy that they also convey. Ladders become sculptural building blocks and Cowardin renders functional objects useless in a delightful, Duchampian tradition. Of course, one reading of the work does not refute the other. Whimsically upending these objects from the built environment feels like an absurdist response entirely appropriate to the current state of the world.

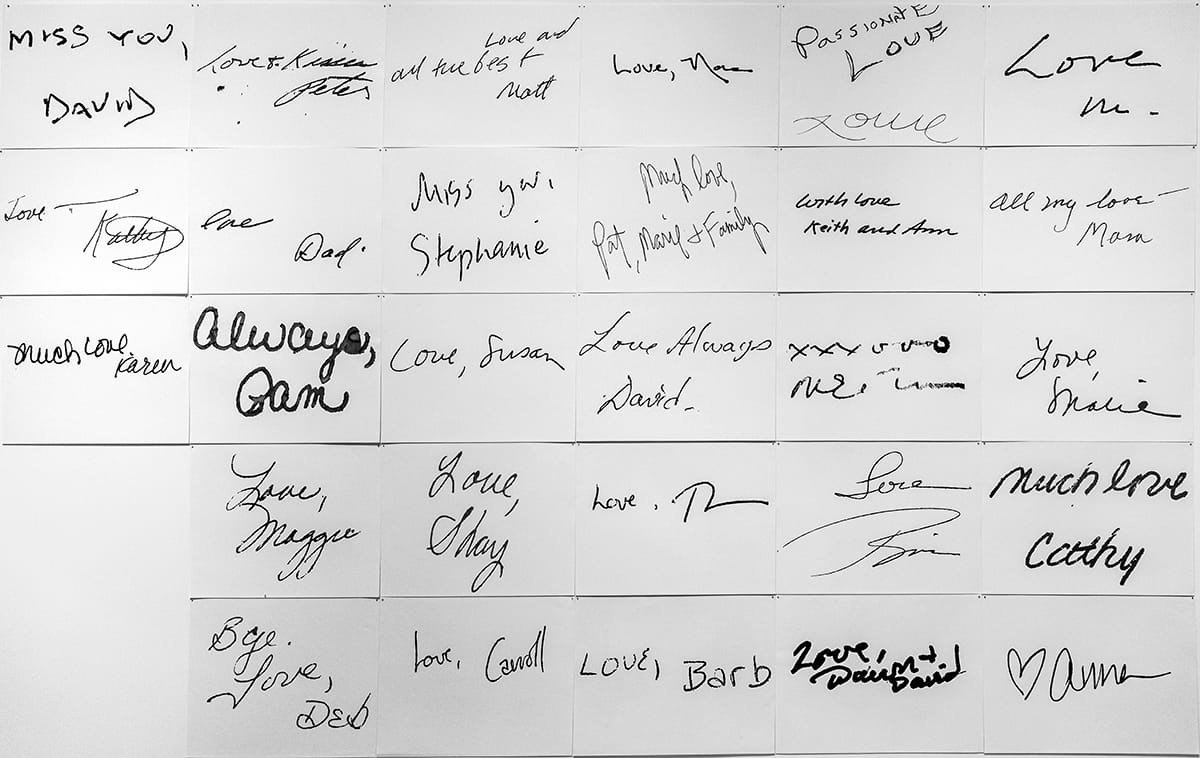

Ann Resnick’s contributions are united not by their materials — text-based ink drawings, burned paper, and spray-painted substrates — but by their underlying theme. I would assert that the entirety of Resnick’s oeuvre deals with grief and absence. Again and again, when I have experienced her work, I have been moved by her meditations on key aspects of the human condition.

In “Untitled 1-3,” Resnick spray-paints stenciled images onto mylar that appear fleeting and transient. The irregular silhouettes prompted me to imagine how the fragile stencils must have fluttered against the force of the spray, lifting off the ground and threatening to disappear. In “Cenotaph (Orange/Green),” Resnick affixes two layers of burnt and painted paper directly to the wall. With bits of greens showing through the burnt areas of orange, it has an organic feeling of autumn, yet the title suggests that it is a memorial to those buried elsewhere.

Ann Resnick, “Dear Ann, Love,” 2011, India ink on paper. Photos courtesy of the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University.

Resnick has long experimented with burning paper. Flames evoke a variety of rich associations: prayer candles, bonfires, eternal flames, cremation, and the simultaneous devastation and cleansing wrought by wildfires and controlled burns. Across the gallery space, in a series of epistolary drawings titled “Dear Ann, Love,” she references the intimacy of handwritten correspondence and the longevity of relationships across decades. The letters become markers of absence as correspondents pass away.

Mona Cliff’s works occupy the least amount of real estate in the show, but her materials speak loudly, nonetheless. In “Conjured Topography,” a cross-section of smooth maple wood stretches nine feet across the wall in an unframed evocation of landscape. The rough, live edge of the wood offers a dynamic foundation for the thousands of seed beads she builds up into forms that call to mind rolling hills or clouds hanging low above the horizon.

If woven baskets are a collective tradition shared by many cultures, Cliff’s beadwork speaks to a more specific cultural practice. As a member of the Gros Ventre (A’aninin) tribe, Cliff learned to bead from her grandmother as part of a tradition that has been passed through generations of maternal relations within the tribe. Using such beadwork to conjure a landscape is an insistent marking of presence, in this moment and in this place, and a material claiming of this place as well.

Beach Museum Director Kent Michael Smith, who curated the exhibition, notes that this is the inaugural Kansas Triennial, suggesting that there will be future iterations. In the publicity for the “Kansas Triennial 25/26,” Smith states that curating a regular series like a triennial “gives us the chance to pause every few years and take stock of what artists in this state are doing, what they're grappling with and how they're innovating. It reflects the incredible depth and range of work being created here in Kansas right now.” While the exhibition highlights compelling work, it is worth noting that three of the four artists are based in Lawrence and the fourth in Wichita. Both cities boast vibrant communities of artists, but I hope that future iterations of the triennial will showcase artists located in other parts of the state as well.

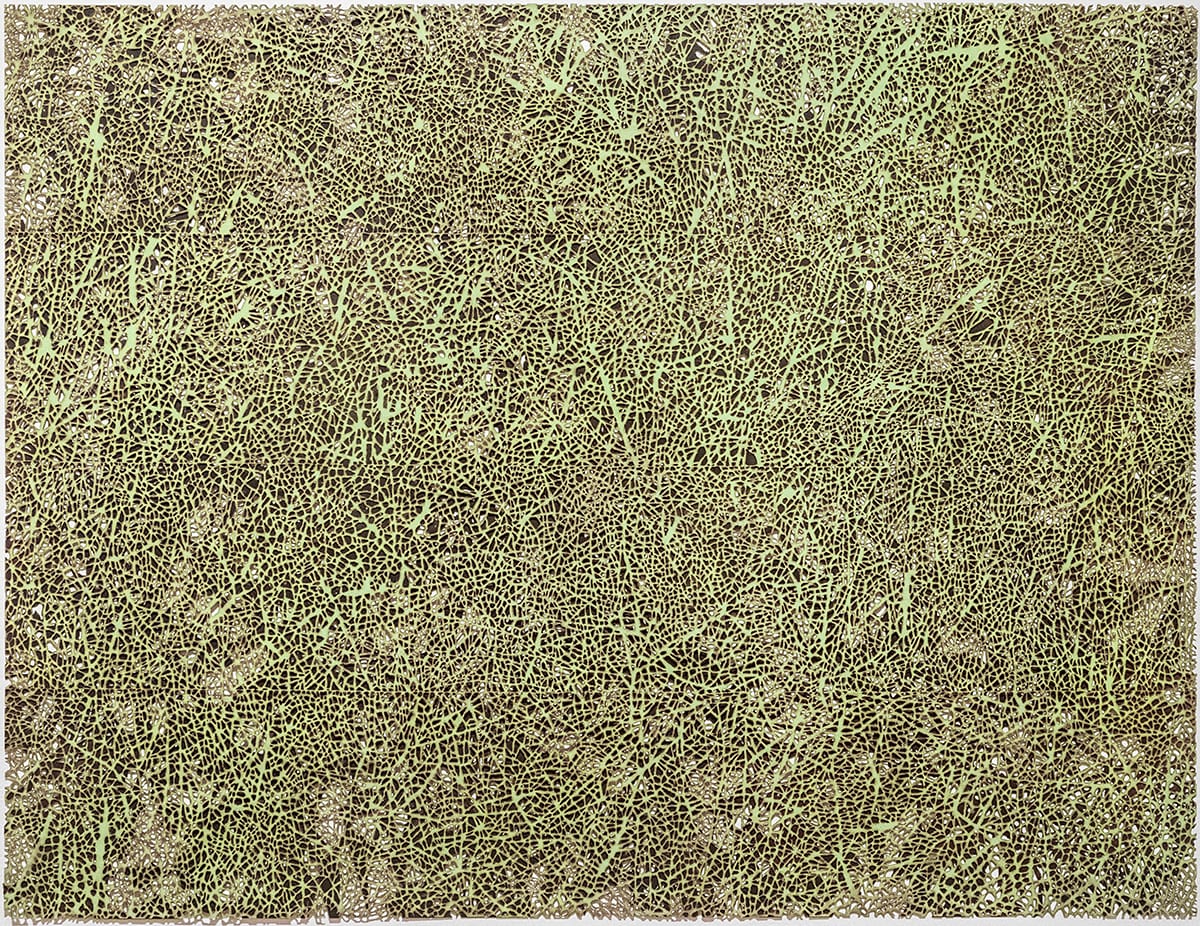

Weeks after seeing the show, I keep thinking about Mona Cliff’s "You Can’t See the Wind," a gorgeous diptych of organic forms. From a distance I saw these images as gestural marks — swirls of paint quickly laid down on canvas before the colors had a chance to mix. Up close, I discovered a different story, one not of rapid movement but of what I imagine as slow repetition.

Cliff strings tiny seed beads and elongated bugle beads onto thread that she affixes to canvas with beeswax and resin. There is a tension between this evidence of repetitive, methodical labor and the visual dynamism of the beads across the surface. Cliff’s title evokes the wind, but the forms also bring to my mind ocean waves or the elegant movements of a painter mid-stroke. Maybe I can revise my earlier observation about the absence of painting in this exhibition. Mona Cliff seems to paint with beads, delighting our eyes with the illusion of colors side by side and offering up a moment of materials frozen in time.

Installation views of “Kansas Triennial 25/26.” Photos courtesy of the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University.

The Details

"Kansas Triennial 25/26"

August 5, 2025-May 31, 2026 at the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, 701 Beach Lane in Manhattan, Kansas

The museum is open to the public from 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday, Wednesday, and Friday, 10 a.m.-8 p.m. Thursdays, and 11 a.m.-4 p.m. Saturdays.

Admission is free, and the facility is accessible to people with physical disabilities.

Rachel Epp Buller is an artist and art historian whose current research explores listening as an artistic method. She is a two-time Fulbright Scholar, a certified practitioner in Deep Listening, and a professor of visual arts and design at Bethel College.

❋ Derby man has the kind of voice that turns heads — and chairs

❋ Socializing while sober: how some Wichitans are cultivating alcohol-free communities

❋ As a small creative business closes, the owner mourns

❋ Painting through it: Autumn Noire on 20 years of making art

❋ How a guy from Wichita resurrected 'Dawn of the Dead'

❋ Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections

Support Kansas arts writing

The SHOUT is a Wichita-based independent newsroom focused on artists living and working in Kansas. We're partly supported by the generosity of our readers, and every dollar we receive goes directly into the pocket of a contributing writer, editor, or photographer. Click here to support our work with a tax-deductible donation.