'Any time there's a celebration, I'm doing henna'

Women in Wichita’s Muslim community observe Eid al-Fitr with the ancient practice of temporary henna tattoos.

A young woman delicately applies henna paste onto the back of an outstretched hand. Her friends and fellow community members are gathered around the table, chatting about their day as they wait their turn. In the background, laughter and excited chatter blend in with the faint sound of the nightly prayer.

It’s Moon Night at the Islamic Society of Wichita (Masjid Al-Noor). Last Monday, women and children gathered in the gymnasium in the late hours of the night to celebrate the end of the holy Islamic month Ramadan.

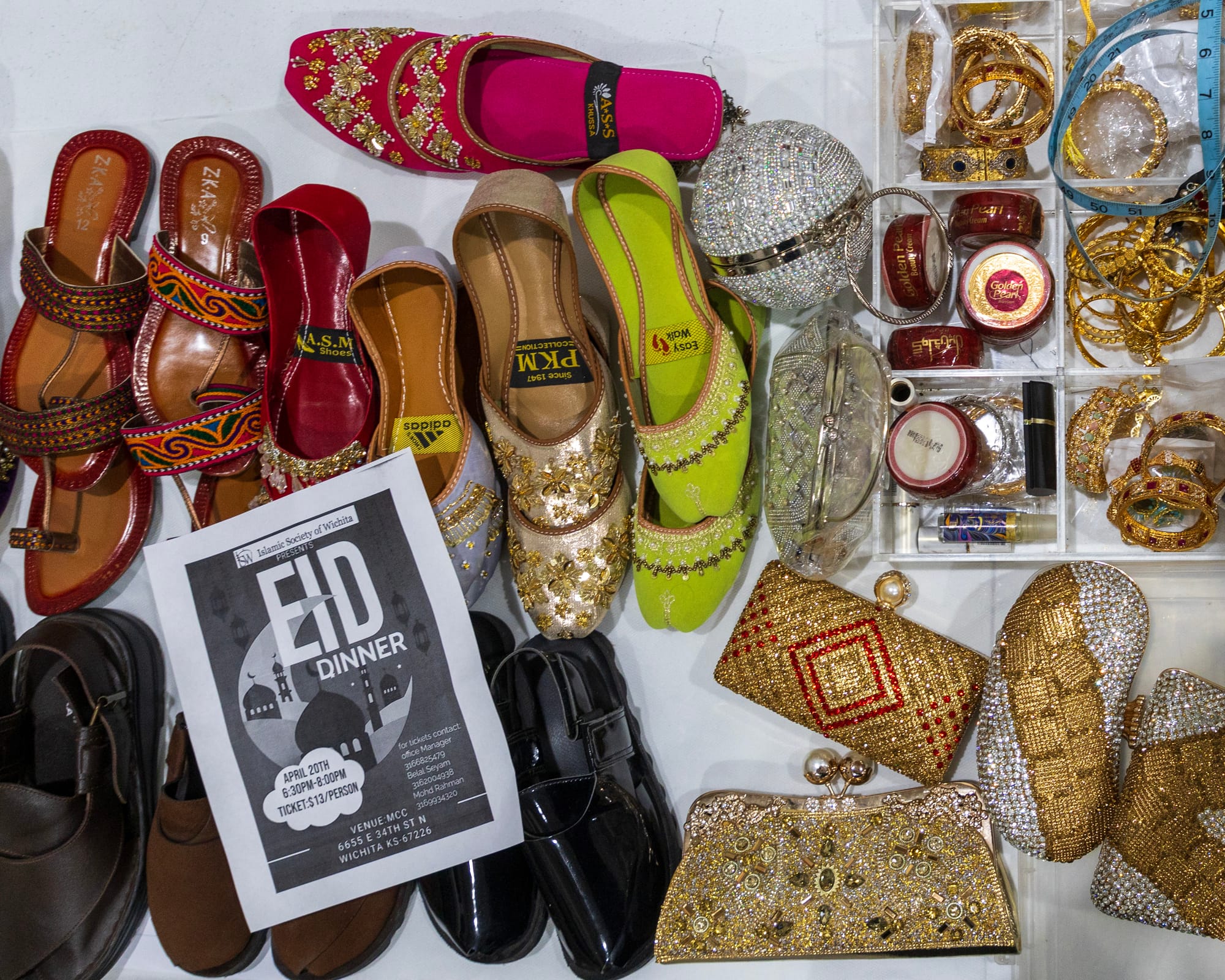

Tables showcase colorful Desi attire, as well as Middle Eastern abayas and scarves. The local aunties and small businesses sell their signature sweets, like date cookies and rasmalai tres leches. Among the crowds of women, teenagers and young children, henna artists carefully apply paste to the backs of clients' hands according to their own style and cultural background.

Muslim women of all ages apply henna in celebration of Eid Al-Fitr, the holy Islamic holiday marking the end of Ramadan. I’m one of them. My fascination with henna began in childhood, when I realized it was another art form I could get into. My mom printed out some hand outlines, and armed with pencils, markers, and a special folder for my henna sketches, I would draw in the corner of the women’s prayer area during Friday prayer at the mosque. I dreamed of becoming a henna artist.

I went on to become a different kind of creative person, but henna has always been a cherished part of my cultural heritage and one of my favorite art forms. I love how dynamic and how endless the possibilities are, given its vast history and varied cultural traditions. It’s something I look forward to every year during Ramadan.

During the holy month, Muslims fast from dawn to sunset. It is a time when we physically, mentally, and spiritually purify ourselves to become the best person we can be. Hundreds of people visit the masjid every night for community dinners and special nightly prayers. Each person also works individually on their personal goals and engages in increased acts of charity.

On Eid day, Muslims gather for special morning prayers at the masjid in their nicest clothes. They exchange greetings of “Eid Mubarak,” meaning “blessed Eid.” It’s a joyous day centered around family, gifts, and food.

Moon Night, which is hosted by the Islamic Society of Wichita’s Sisters Committee, is an annual tradition that takes place two or three days before Eid. At the event, which happens immediately after evening prayers, attendees can buy clothes, food, or get their henna done in preparation for the upcoming celebration.

Wichita State student Zainab Farah Khan is one of the artists who attends every year. She was born and raised in Wichita, and her family is from Bangladesh.

“Henna comes with the culture of the community,” Zainab tells me. “It’s not that literally Eid is incomplete without henna, but it’s become a large part of celebrating for many. For me, personally, I’ve grown up with it. Anytime there’s a celebration, I’m doing henna.”

Zainab’s journey to become a henna artist began at the age of nine during a trip to Bangladesh, where she did henna on someone else for the first time — a swirly lollipop design. Since then, she has honed her skills, showcasing her artistry at events, such as Moon Night and school functions. The day before, Zainab hosted a henna gathering at her home, which is how I got my henna done this year.

On Moon Night, women who already have their henna done browse through the stalls with their friends, their hands lifted in the air to avoid smudging the paste or transferring it onto someone else's clothes. They wait for the paste to dry and stain the skin underneath, which forms temporary tattoos.

Henna paste comes from a small shrub, which grows in a wide range of hot environments. It originated in the Middle East and North Africa. When the leaves are crushed and mixed with water, they release a dye that safely stains the skin, creating a temporary tattoo. While the word henna is Arabic, it's also known as Mehndi in Urdu and Hindi in South Asian countries. Henna, or Mehndi, represents more than just an art form — it's a cultural tradition practiced across generations and cultures.

The paste is typically placed into a cone, and when it's time to apply the henna, the tip is cut off to allow the artist to delicately apply it onto the skin. Depending on the thickness of the lines and the desired color, it can take anywhere from a few minutes to several hours for the henna paste to dry. The longer the paste remains on the skin, the darker the stain will be. Once dry, the paste is gently scraped off, and the design continues to develop over the next few days, until it reaches its full potential. The final color can range anywhere from orange to a deep brown-red, while the design lasts from a few days to a few weeks.

Henna designs vary according to each client's background and personal taste. While natural henna is more traditional, artists also use jagua gel to achieve a darker stain. Photos by Kendra Cremin for the SHOUT.

Every culture uses different motifs in their henna design, utilizing space, layout and line width. Traditional Moroccan henna is more geometric, with full coverage on the hand using triangles, diamonds, dots, herringbone fills, and zigzags. Contemporary Moroccan styles have a Khaleeji (Gulf) influence and are more simple with flowy floral arabesque motifs and shading. Somali henna uses bolder lines and floral motifs with partial hand coverage. While in places like West Africa, a thick layer of henna is applied over thin strips of tape on the skin to create intricate designs, a form of reverse application. Different cultures use black henna or jagua gel instead of natural henna, opting for a darker stain.[1]

Today, henna styles fuse cultures and trends, thanks to the internet. From Afghani to Sudanese, Mexican to Syrian, Indonesian to American, each Eid henna is a testament to the different style and cultural background of each individual.

Henna also plays a significant role in wedding traditions around the world. Many brides adorn themselves with special temporary tattoos in celebration of their nuptials. In Bangladeshi culture, bridal henna features elaborate, full designs that extend up the arms and feet, often hiding the groom's initials within the intricate patterns. These are often detailed spiral and radial motifs of flowers, leaves, vines, and lines. Zainab recently did a fully traditional design for her sister-in-law, celebrating her marriage to the artist’s older brother. It took a total of six hours to complete, and after the henna developed, the bride ended up with a gorgeous dark brown-red stain.

One of Zainab's most involved henna projects was the design she created for her sister-in-law's wedding celebrations. The groom's initials are hidden within the traditional design. Courtesy photos. The photos on the right are by Pixel Works of Bangladesh.

It's also customary to host a mehndi party in Desi cultures as a bridal shower, where henna paste is applied to the bride in celebration of the wedding, accompanied by dancing, music, and food. This is also done in Arab, Central Asian, Southeast Asian, and African cultures as well.

Eman Aljazarah, a member of ISW, fondly recalls her earliest memory of henna at her own Hafla Henna for her wedding more than 35 years ago. Khalto (Aunt) Eman has called Wichita home for three years, having moved here from Jordan to join her husband and son. To her, Hafla Henna signifies new beginnings and showcases tradition and her Palestinian heritage.

One of Khalto Eman’s daughters recently had her Hafla Henna back in Jordan. She wore a veil and gold jewelry over a Tatreez Thobe, a long traditional colorful dress with elaborate embroidery that depicts different motifs within the cross-stitch. In today’s tradition, some grooms are brought into the women-only party to help mix the special henna paste as a part of the celebration.

Khalto Eman prepared a dedicated table in her role as the bride’s mother for the festivities, embellished with bowls of dried henna, olive oil and flower-infused water, which enhance the paste’s staining properties. Joined by their families, the couple blended the ingredients by hand as the women sang traditional songs, symbolizing the unity of their families. When finished with the henna paste, it’s given out as a party favor and the guests give blessings upon the couple.

The bride and groom also put henna on the palm of their hands, usually with each other’s initials and sometimes a simple heart. If the bride doesn’t want a henna design on the back of her hands, she’ll use white henna, which does not contain any natural henna. Instead, it’s made of adhesive and body paint. White or glitter henna is also used on children during Eid celebrations, particularly for those who may find the traditional paste too challenging to keep on their hands until dry.

Khalto Eman also tells me they put henna on her daughter’s chin as a symbol of beauty. It is a nod to Bedouin practices of permanently tattooing women’s chins and/or foreheads for beautification purposes.

Khalto Eman’s other daughter, Jumana Hussein, emphasizes that henna was a major part of her upbringing, from celebrating Ramadan to cherished memories with her grandmother. Jumana and her siblings would eagerly await their grandmother's henna sessions during their sleepovers. Her grandma would prepare a fresh batch, apply it generously to the children's hands, cover them, and let them sleep with it overnight. By morning, they would wake up to find their hands adorned with lovely brown-red stains, a reminder of their grandmother's love and affection.

For Jumana, henna is an essential part of Eid celebrations, adding vibrancy and joy to the festivities. One of her and her mother’s favorite things about celebrating in Wichita is the diversity of the Muslim community here. During Eid prayers at the masjid, traditional outfits from various cultures paint a colorful picture of unity and celebration. It’s one of my favorite parts as well.

Anyone can do henna, just as long as you have the paste. Zainab in particular enjoys creating both detailed and minimalist henna designs. She says that children like to ask for more illustrative designs, like a spider or a cat on a moon. She enjoys the challenge of matching the design to each person.

One of her most memorable requests was for a marriage anniversary. The design itself was inspired by a miscarriage her client experienced. It included floral henna around the inspiration the woman provided. It was a touching experience for both Zainab and her client.

Zainab’s rates can vary anywhere from $10-$30 per hand, depending on the complexity and size. Given the intricate nature and significance of bridal henna, she sets a higher fee for these time-consuming, specialized designs. She shares her work and connects with new clients on her Instagram account.

Eid Mubarak to Muslims worldwide, and may the art of henna continue to bring joy and beauty to your lives.

In addition to henna, Moon Night offers opportunities to shop for new clothing and jewelry and purchase food and sweets to enjoy during Eid-Al-Fitr. Photos by Kendra Cremin for the SHOUT.

Masara Al-Sharieh, a Wichita native of Jordanian-American heritage, earned her degree in Collaborative Design from Wichita State University. Currently working in marketing and event coordination, Masara's focus is on inspiring growth, creativity, and community engagement. She enjoys traveling, savoring coffee, and exploring local Wichita gems.

1.It's wise to exercise caution with black henna or any store-bought henna, as they may contain harmful chemicals such as para-phenylenediamine. Fruit-based Jagua gel is another safe option if looking for a darker stain.