'Just Willa': Like mother, like daughter

A new novel by Wichita native Helen Sheehy explores the lives of early 20th-century Kansas and Oklahoma farmers and ranchers. Technically fiction, “Just Willa” drips with the kinds of details that the best historians mine from deep research.

As soon as she could escape, 18-year-old Helen Sheehy got the hell out of Dodge — or, more precisely, the southern Kansas tenant farm of her childhood, where her mother had worked herself to the bone sunup to sundown. Sheehy fled to Wichita, graduated from Wichita State, taught theater and English at North High, and finally ended up in Connecticut, where, in addition to writing for a swath of prominent publications, she taught theater at Southern Connecticut State University for more than two decades. Best known for her biographies of theater pioneers Margo Jones, Eva Le Gallienne, and Eleonora Duse — the latter two named New York Times notable books of the year — she recently published her first novel, set in the scrappy, tiny Dust Bowl farm towns that were home to multiple generations of her family.

By Sheehy’s own admission, the reason “Just Willa” is fiction is because the material she needed to write the kind of meticulously researched nonfiction that has won her acclaim simply wasn’t there. But the “fiction” of this novel is thinly veiled.

“The playwright Connie Congdon said, ‘All fiction and all true,’ ” Sheehy said at an April appearance at Watermark Books, one of her book-tour stops to promote her novel. (It also was one of the final events hosted by longtime Watermark owner Sarah Bagby before her retirement.)

“This is based on my mother, but it is fiction,” Sheehy said. “After my mother died, when I was 36, I realized that I really didn’t know her very well. I had written three bios of complete strangers who I knew better than my own mother. So, I decided to research her as if I were doing another bio. I went back to Freedom, Oklahoma — my mother’s father was a homesteader there and helped found the town. I walked around, talked to people, got interested in my father’s life: He was a cowboy, a bootlegger, and a boxer. But I didn’t have enough material to write a true story, so I decided to use my imagination.”

Subscribe to our free email newsletters

Stay in the know about Wichita's arts and culture scene with our Sunday news digest and Thursday events rundown.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

That imagination centers the story in Freedom and later Protection, Kansas, viewed mostly through the titular character’s eyes. Although Willa’s experiences comprise the bulk of the storyline, the book’s arc stretches across nearly a century, revealing the working lives of farm and ranch communities in the early 1900s. The characters are often stupid, dishonest, selfish. (A man runs liquor in cahoots with a state senator despite explicitly promising his wife not to. He also shoots himself in the leg.) They are also strong, unbreakable, intuitive. (A mother who reluctantly ended her education at eighth grade on her father’s orders instinctively knows the best approach for a daughter fighting schizophrenia, her wisdom dismissed by her husband and their doctor.)

Willa puts in more manual labor between sun-up and breakfast than most of us manage in an eight-hour day. And then she moves on to the serious day’s work. Poverty, loss, her own body’s inevitable betrayals — her encompassing cure for them all is work.

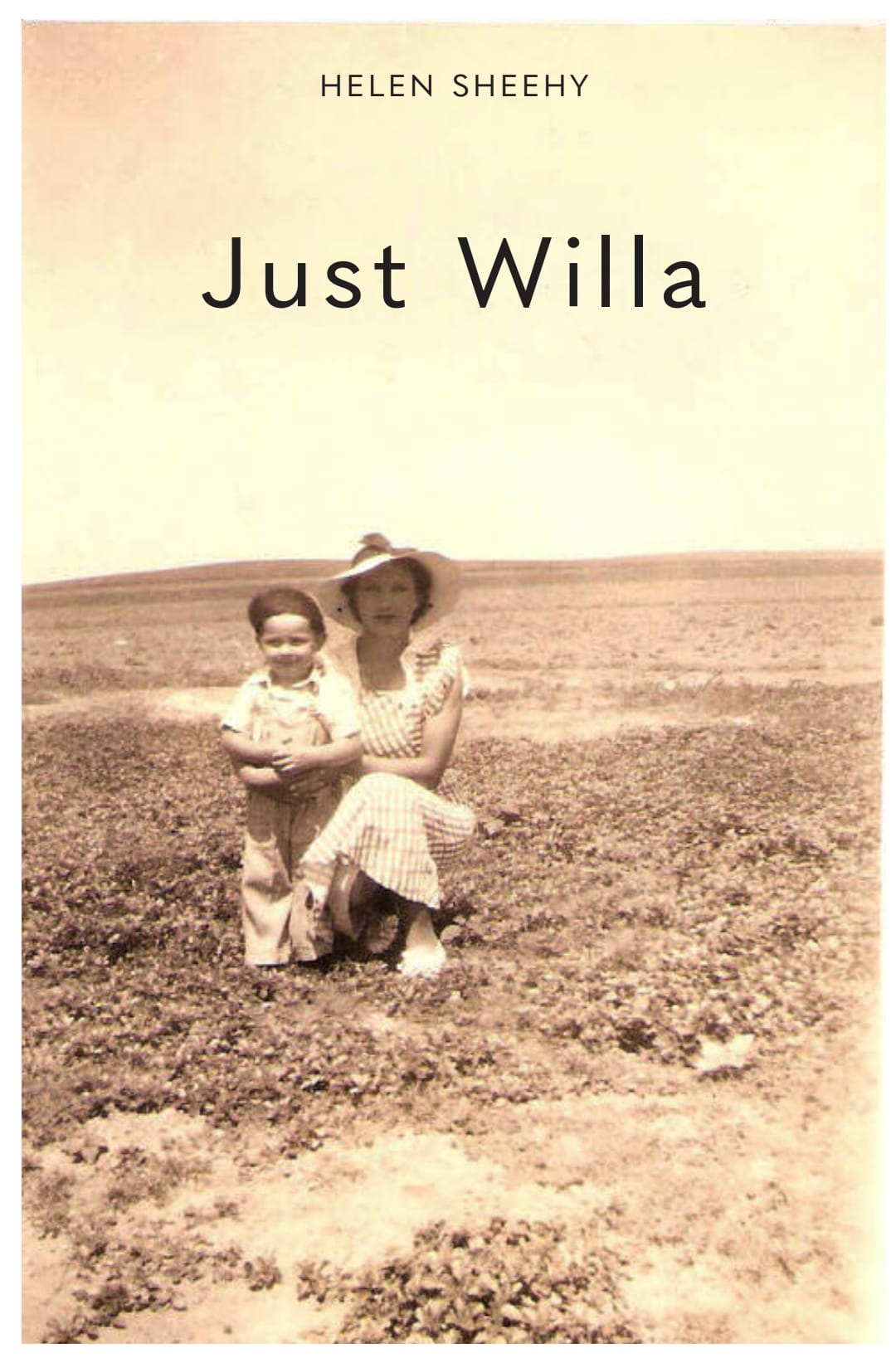

Helen Sheehy's first novel is based on her family's history in tiny Dust Bowl towns in the Great Plains. "I didn’t have enough material to write a true story, so I decided to use my imagination," she said. Images courtesy of the author.

Kansans might be surprised at some of the book’s depictions of our state and its inhabitants, particularly our racist and classist treatment of the Oklahomans who moved here within the book’s timeline. While it is a narrowly defined story of a particular family at a particular time, the presence of Native people in Oklahoma is a thread in the story’s tapestry. Select members of Willa’s family are routinely described as “dark.” Provenance theories center around when, not if. (Her grandmother’s mother? Her mother?)

At her Wichita appearance, Sheehy said that early in her book’s development, she fretted about whether or not anybody would care about an ordinary woman in a small Midwestern town. After one of her biographies had been published to favorable reviews, she’d been asked to speak at a gathering in New Haven, Connecticut.

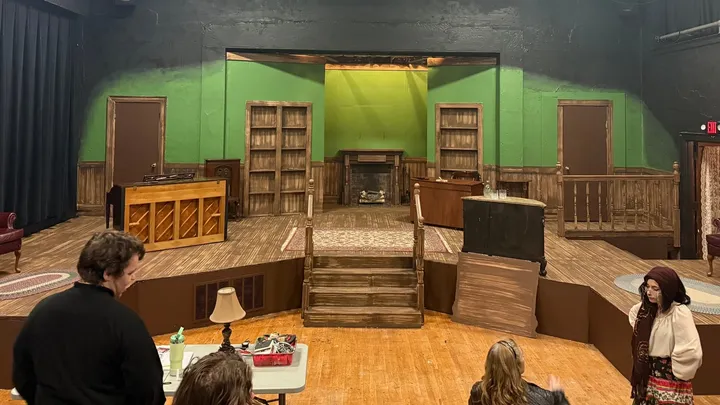

Sheehy discussed her novel at an appearance at Watermark Books & Cafe last month. Photos courtesy of the author.

“They wanted me to end with a bit about what I was working on now,” Sheehy said. “So, at the end of my 40 minutes, I told them about Jake and Willa and about this period. At the end of the talk, not one person asked about my writing being included on the New York Times Notable Books list. Nobody cared. They wanted to know what happened to Willa and Jake. What did that phrase mean, ‘the Oakies who stayed’? That gave me the courage to keep writing. If these women in New England who probably never set foot on a farm cared about this woman, I did too. It took me 20 years to finish it.”

At Watermark, Sheehy eschewed the traditional ritual of reading selections from her book. Instead, she held a “conversation” with her longtime friend Dave Stone:

Sheehy: “I’ve known Dave since we were in a production of ‘The Moon is Blue’ at Wichita State University. I played a professional virgin — and I didn’t shut up for three acts.

Stone: “How about 40 years?”

The Details

"Just Willa," a novel by Helen Sheehy

440 pages. Published April 13, 2025 by Cave Hollow Press.

At press time, "Just Willa" is in stock at Watermark Books & Cafe, 4701 E. Douglas Ave.

Anne Welsbacher writes plays, nonfiction, and book and theatre reviews. She can be found on Substack and Bluesky. She is the Performing Arts Editor for this publication. awelsbacher.com

Support Kansas arts writing!

The SHOUT is a Wichita-based independent newsroom focused on artists living and working in Kansas. We're partly supported by the generosity of our readers, and every dollar we receive goes directly into the pocket of a contributing writer, editor, or photographer. Click here to support our work with a tax-deductible donation.

⊛ Off-Broadway, a Kansas playwright meditates on the labor that defines us

⊛ Wayne Gottstine is 'back in the fight'

⊛ Star of MTW's 'Gypsy' finds purpose both on stage and from behind a pulpit

⊛ 'You don't have to give up': Clark Britton on making art into his 90s

⊛ Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections

The latest from the SHOUT

The SHOUTSam Jack

The SHOUTSam Jack

The SHOUTTeri Mott

The SHOUTTeri Mott

The SHOUTTeri Mott

The SHOUTTeri Mott

The SHOUTShelly Walston

The SHOUTShelly Walston