Exhibition traces the history of Mennonite immigration to the Midwest

Family heirlooms, travel items link immigrant stories to lives in the Midwest at the end of the 19th century, on view at the Kauffman Museum at Bethel College through June 1.

"Unlocking the Past: Immigrant Artifacts and the Stories They Tell," at the Kauffman Museum in North Newton, Kansas, foregrounds the stories of Mennonite immigrants. The museum is located on the campus of the 138-year-old Bethel College, the oldest Mennonite college in North America. Bethel has a long connection to the immigrant experience: Many early students hailed from Germany, Russia, and Switzerland.

The presentation of the exhibition lines up with the 500-year anniversary of the emergence of Anabaptists in Europe (Mennonites are descendants of the Anabaptists), as well as the 150-year anniversary of the mass migration of Mennonites from Russia and Prussia to North America. As a native Wichitan and regular visitor to Newton, I knew Bethel was Mennonite-founded. But many area residents may not know that the Mennonites were forcibly removed from their homelands for their pacifist practices and their doctrine of baptism by election.

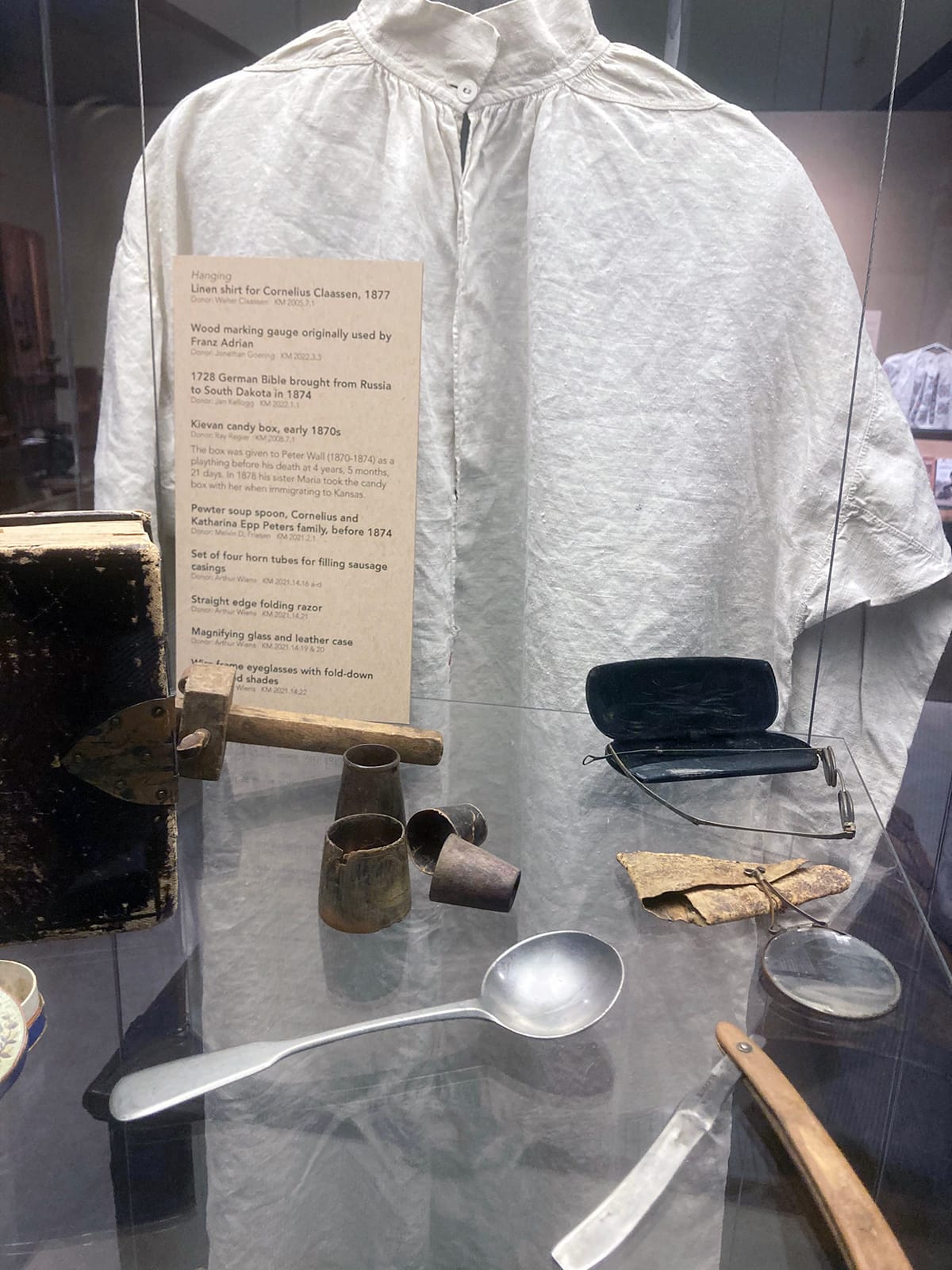

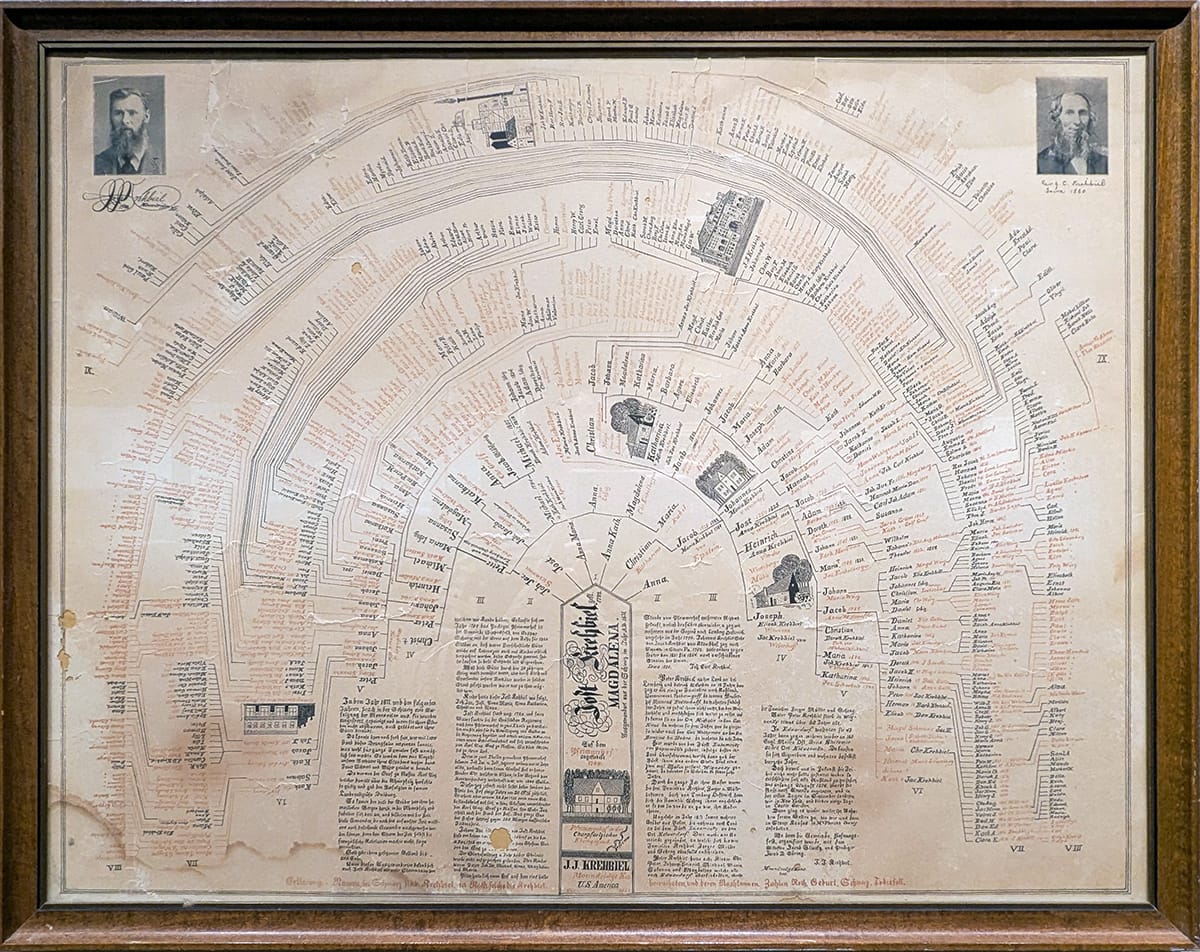

Installation views from “Unlocking the Past: Immigrant Artifacts and the Stories They Tell."

The opening artifact is a facsimile of a Mennonite family Bible that dates back to the early 1500s — the original Bible is out of view, being restored — and this weathered item sets the stage for how deeply entrenched the desire for religious freedom was for those traveling to new lands in the late 1880s. Families set sail to Canada and the United States. The separation of the Bible with a sail-covered curtain from the rest of the exhibition reflects this vast distance the families put between their homelands and their new settlements.

Perhaps the most prominent pieces of the exhibition, and those that fascinated me most, are the nearly two dozen wooden and worn travel trunks, dowry chests, and suitcases used by those migrating west. They range in size from more than three-feet wide and two-feet deep to smaller, handheld cases. Their heft — most made of solid wood with metal hinges — and their intricately lettered addresses belie the psychological weight of migration. These individuals migrated not only to start afresh but to save their lives from those persecuting them for the pacifist refusal to enlist in the military, as well as the ethnic cleansing in Russia and Germany dating back as far as the middle 1600s.

From left: Peter Funk travel trunk, wood with metal hinges, lattice work and faded address lettering. 36 by 30 inches; Funk travel trunk, wood and metal hinges with white address lettering, 30 by 24 inches; a Funk dowry chest, wood, 40 by 24 inches, filled with linens, a kettle, woodworking tool, and other items. Photos by Shelly Walston for the SHOUT.

And while the chests are physically large, their presence also emphasizes how few items these individuals were able to bring with them across the ocean and into the Midwest. Entire lives had to fit into parcels of twelve cubic feet: linens, a Bible, a samovar or tea kettle, a musical instrument, woodworking tools, a few articles of clothing per family member, and the necessities to rebuild their lives. Some families, like the Jansens, were able to ship a whopping 47 pieces of luggage, while others had much smaller collections.

Also on display is the Jansen family samovar, one of the prominent items they brought to North America. Adjacent to the brass samovar and tray — large in stature at more than 2 feet tall — is a family photo of the Jansens. The nine family members sit closely together, adults draped in dark formal wear and children in lighter yet no-less-formal clothing. Indeed, the proximity of family members, sitting somewhat austerely — it was the 1800s after all — highlights the importance of the samovar, a percolator used for making tea. A chance to take a break from the difficulty of farming and woodworking, to sit around the samovar and enjoy a cup of tea, this artifact calls attention to bringing family and community together. It’s clear that close-knit families made for close-knit communities, bound together by their love of religion and hospitality towards one another.

The museum’s exhibit puts a spotlight on five families — all Mennonites — who migrated through Canada and into Kansas, Indiana, Illinois, and Nebraska: the Jansens, the Krehbiels, the Funks, the Warkentins, and the Rempels. Each of the men in these families were leaders in the Mennonite communities that later grew out of the settlements they joined. Their artifacts indicate what more affluent Mennonites were able to bring with them. Less well-to-do community members are not as well represented in this exhibition.

Subscribe to our free email newsletters

Stay in the know about Wichita's arts and culture scene with our Sunday news digest and Thursday events rundown.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

I appreciated the inclusion of information about how Mennonite immigrants displaced first Kansans: the Kanza, Pawnee, Wichita, and Osage. The exhibition includes maps acknowledging the land formerly held by Indigenous people.

Many artifacts highlight the importance of home life, down to the bricks and sod used to build their houses and the wood to craft their furniture. A large corner is devoted to such artifacts: from the blueprints and the bricks used to construct a church in 1880 in Inman, Kansas to the doorframe of a home, ornate clocks with floral designs and brass pendulums, as well as the indigo-dyed clothes one might find on a clothesline outside of a property.

Beyond the trunks and building materials, various ephemera populate the glass cases in the exhibit, and one such item of intrigue is the Life Awakener. This tool, a 10-inch tube of ebony wood with a 20-needle tip and a removable cap, was used for dental and skin issues. In fairness, however, it looks more like a medieval torture device. Practitioners would dip the needle tip into antiseptic and then pierce the skin of their patient to “release bad humors” and drain “health destroying morbid matter,” according to an accompanying booklet adjacent to the glass cabinet. The Life Awakener was initially popular in Mennonite communities, but it fell out of fashion with the advent of medical advancements.

Less prominent are the furniture-making tools used by these immigrant Mennonites; however, there is a large wardrobe, approximately six-feet tall by four-feet wide, from the Entz family with impressive scroll work and inlaid wood — a piece only made possible by the meticulous and impressive woodworking skills for which the Mennonites are known. For a more in-depth look at woodworking tools and traditions, the Kauffman Museum’s permanent exhibit, “Mennonite Immigrant Furniture,” is located adjacent to “Unlocking the Past” and well worth the visit.

In addition to the physical pieces on display in “Unlocking the Past,” the Kauffman Museum has hosted 12 lectures about migration stories on Sunday afternoons for the duration of the exhibit. The last in the museum’s lecture series will take place at 1 p.m. Sunday, May 11. Valerie Mendoza will discuss “Stories of Mexican Migration to Kansas.” Admission is free.

The Details

“Unlocking the Past: Immigrant Artifacts and the Stories They Tell”

Sept. 29, 2024-June 1, 2025, Kauffman Museum at Bethel College, 2801 N. Main St. in North Newton, Kansas

The Kauffman Museum is open to the public from 9:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m. Tuesday-Friday and 1:30-4:30 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays. Admission is $5 for adults and $3 for children ages 6-16.

Shelly Walston is an educator, reader, writer, and collector of commemorative state plates. She's been teaching English at the high school level for more than two decades. When not grading essays, working on her novel, walking the dogs, or playing strategy games, you'll find Shelly sprawled on her couch, reading a book. More of her writing and book reviews can be found at shellywalstonwrites.com.

⊛ Off-Broadway, a Kansas playwright meditates on the labor that defines us

⊛ Wayne Gottstine is 'back in the fight'

⊛ Star of MTW's 'Gypsy' finds purpose both on stage and from behind a pulpit

⊛ 'You don't have to give up': Clark Britton on making art into his 90s

⊛ Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections

The latest from the SHOUT

The SHOUTLeslie Coates

The SHOUTLeslie Coates

The SHOUTJessy Clonts Day

The SHOUTJessy Clonts Day

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTAbby Bayani-Heitzman

The SHOUTAbby Bayani-Heitzman